Generally, I don’t take requests at Synaptic Space. I have a huge backlog of topics I want to write about and I’m usually very busy following my own curiosity down some twisted trail of inquiry. When my eight year old son asked me to write something about lasers, though, it seemed incredibly relevant to my mission here. The tale of the laser’s journey from the pages of fiction, to theoretical concept, to physical reality is one of those instances where myth and fiction have conspired to push forward the bounds of reality. So, my boy, this one’s for you.

My son has begun to notice that lasers are everywhere. They are unquestionably the weapon of choice for many of the characters in the shows and movies he likes to watch. But they are more immediately present in the blu-ray player that reads the disk encoded with the images and sound that bring those shows to life. When he presses play on the remote control, he is shooting invisible lasers that command the unit to play. Sometimes he watches movies on Netflix where he is seeing the result of information that has traveled at the speed of light through a vast network of fiber optic cables carried from a server to our TV by precision lasers. When we go to the store to pick up the popcorn before the movie, we swipe the package under a scanner that uses lasers to read information from a barcode containing product and price information. After the movie, he and his brother like to reenact scenes, often using laser tag toys that fire invisible photons at each. Often he goes to visit his grandmother who is now able to drive him to her house because her once terrible vision has been corrected by surgery performed with high-powered laser beams.

It’s fair to say that lasers have become a fundamental part of our society, though what they are and where they come from is hardly common knowledge. The word “laser” is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. In plain English, they are devices that increase the power of light energy (Light Amplification) while focusing it into a coherent beam (Stimulated Emission of Radiation). Where light coming from an electric lamp or wax candle is emitted in random wavelengths, directions, and from all over the color spectrum, a laser organizes the flow of energy into a uniform pattern from a single color of the spectrum, and channels it into a beam that travels in a thin straight line.

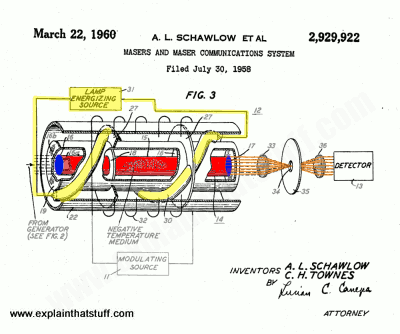

- Early laser patent filed by Charles Townes and Arthur Schawlow, July 1958.

But of course, if you’ve read any of my previous posts here, you’ll know I’m not about to limit my discussion of this technology to either its physical properties or its practical applications. The laser is with us today not just because physicists and engineers found a way to create it, but because dreamers first conceived of its existence and then wove their dreams into imaginative tales. As interesting as the checkout scanner that allows you to more easily buy a pack of gum is, you are undoubtedly here to read about blasters and light sabers.

The question of how light can be harnessed as a tool is as old as our species. No one knows exactly when human beings (or their hominid ancestors) first domesticated fire, but up to that point, the sun and to a lesser extent the stars were the sole source of illumination. Even after human beings settled into organized civilizations it wasn’t until the last few centuries where light was always readily available once the sun set. Euclid tried to better understand the properties of light and reported his findings in a treatise on vision from the fourth century BCE entitled Optics. Greek and Islamic philosophers stood on his shoulders and worked through careful observation to build on that knowledge. In 1672, Sir Isaac Newton wrote that light was made up of tiny particles. Eighteen years later, Christian Huygens countered that it was made up of waves. In 1905, Einstein proved that it was both.

For most humans throughout history, though, light was an almost magical entity. It isn’t surprising then that light deities and sun gods are ubiquitous across human cultures. The Greeks had Apollo. The Norsemen had Balder. In Egypt there was the sun-god Horus. The Mesopotamian solar-god Shamash illuminated concepts of justice to Hammurabi. Australian aborigines look to Gnowee, a mother whose divine torch illuminates the entire sky in search of her lost child; in the influential ancient Chinese text Huainanzi, the sun-goddess Xihe illuminates every aspect of life as she guides her sun chariot across the sky. Aztecs tried to put off the apocalyptic urges of the solar deity Huitzilopochtli with the blood of human sacrifice. Some gods managed to harness light into potent weapons. Ancient Greeks reveled in war stories about Zeus’ powerful lightning bolt and the Vedic god Indra wielded a strange and mysterious weapon called the Vajra that was believed to harness divine light into a destructive force. In Irish mythology, the sun god Lugh carried a spear that was so full of deadly light that it needed to be kept in water when not being used in battle lest it burst into flames. His one-eyed enemy, Balor whose “death eye” is said to bring an instant end to any foe he gazed at, was often depicted firing a destructive beam of light.

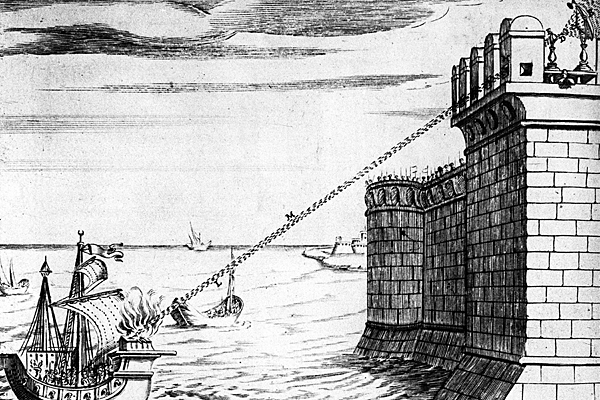

Perhaps the first historical claim of human beings harnessing the power of light into a weapon comes to us from around 214 BCE. The Greek city-state of Syracuse was home to Archimedes, one of history’s great engineers. The legendary polymath was usually focused on purely intellectual pursuits like calculating the value of pi or elucidating basic principles of hydrostatics. But when hostile Roman legions came to Syracuse in search of conquest, his intellect was called upon for the more practical task of defending his city. Legend tells of various war machines he conceived and designed, including a giant claw that plunged Roman ships into the sea and a wide array of high tech versions of catapults and other anti-siege devices. The most intriguing of these was his so-called death ray; a series of mirrors were set up on the city’s walls and angled to capture sun light and focus it into a single, high energy beam that was directed towards Roman ships to set them ablaze. Historians have disputed the accuracy of the story, suggesting that his weapon was actually Greek fire shot from a steam cannon or some other conventional defense. Engineers have tried to recreate the death ray with mixed results and Mythbusters found the tale to be bunk. Whether or not the people of Syracuse did use such a weapon, the possibility that energy might be directed into a weaponized beam has been debated since at least the middle ages.

If there were an award for the work that deserves the most credit for creating the science fiction genre, my vote would go to H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. The 1897 novel gave us one of the first examples of Earth being invaded by deadly alien invaders. Wells’ hideous Martians brought with them a weapon that would become iconic throughout the subsequent history of science fiction. In a chapter entitled “The Heat-ray in The Chobham Road” Wells describes a weapon of “intense heat” that causes victims to become “charred and distorted beyond recognition”. The invaders use their weapon to put up an irresistible defense that annihilates people and cities in the millions before succumbing to the common cold for which their bodies had no natural immunities. The story’s narrator that the weapon is able “to generate an intense heat in a chamber,” that allows it to “project in a parallel beam against any object (the Martians) choose.” This description is not far off from that of the basic design used in the lasers invented decades after the novel’s publication.

- Illustration from 1906 edition of War of the Worlds by Henrique Alvim Corrêa

In 1917, Albert Einstein published a paper called “On the Quantum Theory of Radiation” that laid out the mechanism for stimulated emission of light. Einstein had argued a decade earlier that light traveled in packets of energy called photons. With this paper, he introduced the fundamental concept of how electrons could be stimulated and forced to release a massive numbers of photons that would travel in a uniform wave to produce a concentrated beam of light. But theoretical constructs do not always easily translate into real world applications. It would be more than four decades before the door of possibilities created by Einstein’s paper was fully opened.

Storytellers are not constrained by the same obstacles as scientists. Around the same time, the genre of science fiction was being birthed in the pages of pulp magazines and on the airwaves of radio serials. Born of 19th century scientific romances and of the works of writers like H.G. Wells, the emerging genre took concepts like rocket ships, jetpacks, and time machines, and turned them into standard tropes. The Martian heat rays from War of the Worlds proved to be one of the most enduring of these, inspiring sci-fi’s signature weapon, the ray gun. The term was coined by Victor Rousseau in his short story “The Messiah of the Cylinder”, published in the same year that Einstein released his groundbreaking paper. Ray guns were not necessarily lasers, but generally referred to directed energy weapons that focused electromagnetic waves into a powerful beam that fired from both mounted cannons on spaceships and handheld pistols and rifles. In his popular radio serial, Flash Gordon used a ray gun while Buck Rogers used the more descriptively-named, “disintegrator” (which became one of the most popular toys of the 1930s). E.E. “Doc” Smith’s characters used a needle-ray projector in his Skylark series that was serialized in Amazing Stories during the 1920s. John E. Campbell, Amazing‘s editor, made ray weapons a standard in the pages of his influential magazine from about 1930 onward. From there, a wide array of variation on the energy beam weapon became regular sci-fi fare. Amazing Stories and other magazines featured endless types of heat beams, freeze guns, shrink rays, blasters, disintegrators, and death rays. There were beams that could paralyze single victims, and others that could vaporize entire planets. Robert Heinlein had a specialized ray gun that could recognize the racial categorization of its enemies in The Day After Tomorrow. The pain rays from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series that could disable enemies was powered by a tiny nuclear reactor.

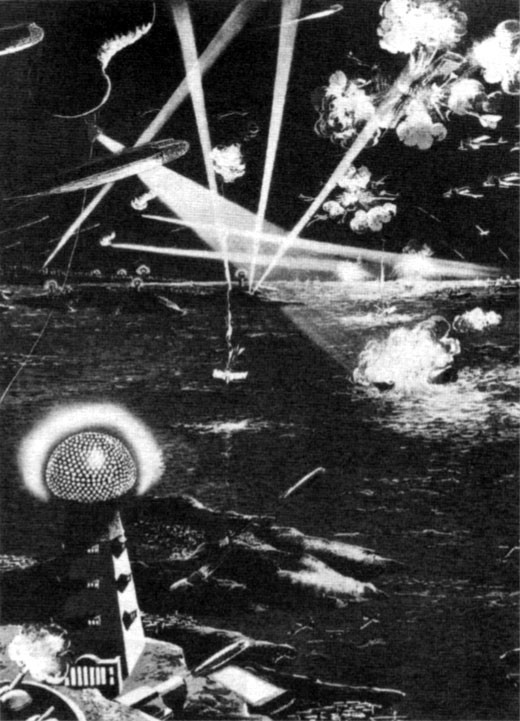

In 1934 Nikola Tesla seemed to bridge the gap between fictional energy beams and theoretical science when he revealed plans for a device that would “send concentrated beams of particles through the free air, of such tremendous energy that they will bring down a fleet of 10,000 enemy airplanes at a distance of 250 miles”. This was not an actual laser, but rather a particle beam whose destructive ray was made of matter rather than light energy. Tesla called his theoretical invention a “peace beam” and imagined it would make war less destructive by serving as a deterrent because of its devastating potential. The press did not share his Utopian vision for the device, and referred to it instead as a “death beam”. Various governments expressed interest in developing Tesla’s ideas, though it is doubtful that they shared his humanitarian motives. Hitler’s invasion of Poland and the ensuing events of the next decade (as well as Tesla’s death in 1943) did away with any widespread interest in a “peace beam”.

- Tesla’s imagined view of future warfare as illustrated by Paul Frank from Science and Invention, February 1922.

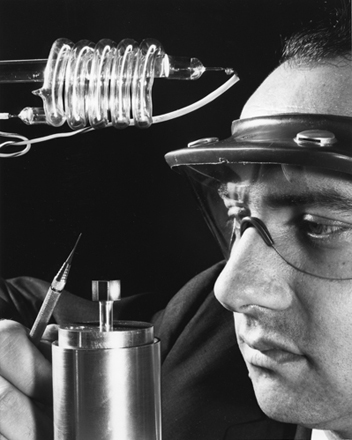

In 1960, the gap between the visions of Wells and Einstein was closed when Theodore Maiman (working with a modified design patented two years earlier by Arthur L. Schawlow and Charles H. Townes) invented the first working laser by applying energy from a xenon flash lamp to a synthetic ruby cylinder bookmarked with mirrors. Large numbers of photons were released from excited electrons inside the crystal and funneled through a narrow opening in the form a single line of red light; the world’s first working laser. It was quite an achievement that would eventually pay major dividends for the coming digital age, but at the time, Maiman’s invention had very little practical application.

But fiction writers found immediate use for Maiman’s invention. The 1964 film James Bond film, Goldfinger, was originally scripted with a scene that featured the hero about to be cut in half by a table saw while his nemesis delivered the classic line, “No Mr. Bond, I expect you to die”. But on the heels of the new invention, the means of Bond’s bisection was changed to that of a lethal red laser beam. Genre science fiction jumped in, easily phasing its vast array of ray guns and energy beams into laser weapons. Clifford D. Simak’s hero, Enoch Wallace finds himself in a gun fight with a laser-armed alien in his 1963 novel Way Station and the Imperium in Frank Herbert’s sprawling Dune series (starting in 1965) were armed with “lasguns”. Science fiction television shows from the 1960s like Lost in Space made use of laser pistols and the officers aboard the Enterprise in Star Trek carried the similarly named, phasers. A decade later, George Lucas’ space opera, Star Wars popularized the laser in multiple forms; from handheld blasters to the planet-destroying Death Star beam, to the iconic weapon of the Jedi Knights, the light saber, the laser was central to the story. Laser weapons in endless varieties continue to be mainstays in science fiction in every medium.

- Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader meet for their first lightsaber duel in The Empire Strikes Back, 1980.

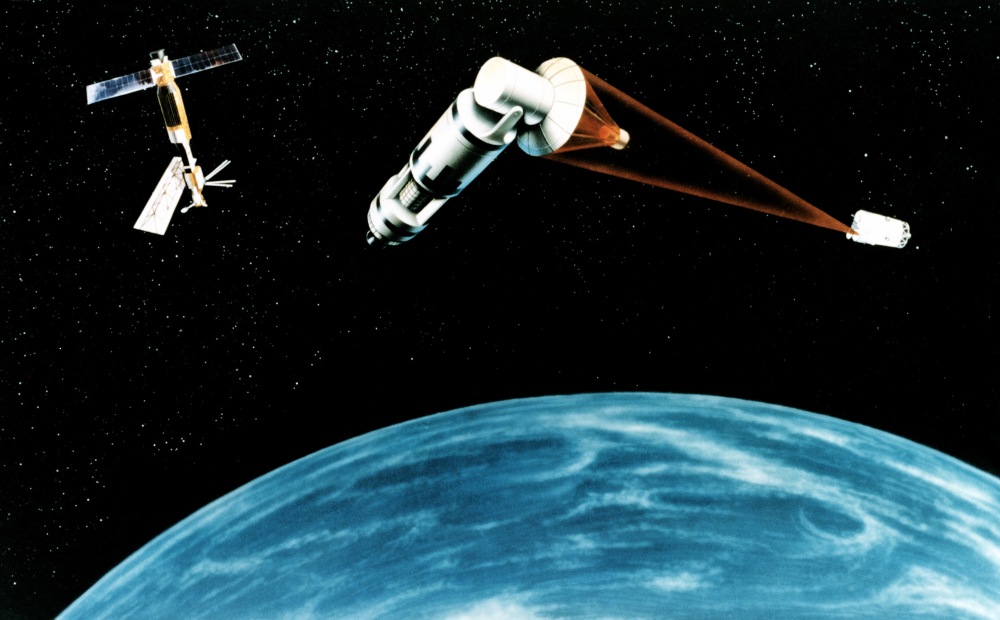

It was only a matter of time before lasers were making their way into medical and industrial uses that lacked in the sort of thrilling applications provided by science fiction stories. But human beings have a tendency to weaponize just about everything. Where science fiction had provided such a sprawling array of possibilities, it was inevitable that these weapons of fantasy would end up on the drawing boards of designers and engineers. In 1983 the Reagan Administration announced plans for The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). Nicknamed the Star Wars program, the plan proposed launching devices into space capable of firing a laser or particle beams designed to shoot down ballistic nuclear missiles launched from the Soviet Union or other hostile forces. The plan was immediately attacked by the administration’s opponents for its potential to reignite the nuclear arms race and called out by physicists as being impractical, requiring technology that was decades away from realization. The project was cancelled in the late 1980s without ever launching any lasers into space.

This does lead us to the glaring gap between fantasy and reality that often accompanies the transition of science fiction technology from the page or screen to the field. Real life has come to resemble the worlds of early science fiction in many ways. Most of us carry hand-held communications devices in our pockets and self-driving cars are now zipping around our streets. There are voice command systems that play songs, turn on lights, and look up information for us that answer to names like Alexa and Siri. Yet, even though we’ve put humans on the moon by flying the sorts of rockets that Jules Verne and H.G. Wells dreamed of more than a century ago, we are a far cry from the vast possibilities of space travel that early science fiction authors believed were on the horizon. We have created robots able to complete increasingly complex tasks, but they still lack the agency given to them by Isaac Asimov more than a half century ago. Similarly, lasers are a vital building block of modern civilization, but they are much different from the fictional weapons that are a standard feature in science fiction stories.

Lasers are currently used heavily in guidance systems used to improve the accuracy of conventional weapons, but the military planners of the world are still a long way from firing death rays at hostile forces. According to a New York Times article from 1981, “It’s just silly. It takes more energy to kill a single man with a laser than to destroy a missile.” With today’s technology, the energy requirements for large mounted laser cannons would require an energy source that would need to be the size of a large vehicle. This does call into question the possibility of ever seeing sort of hand-held laser weapon that every sci-fi dork has ever dreamed of. For now both the dream of Tesla to make war a thing of the past and the probable nightmare reality that would actually accompany the development of laser weapons remains on a far horizon.

Nonetheless, lasers will continue to be the basis of new technologies that will improve our communications, energy efficiency, entertainment and healthcare. But we are not likely to see any real-life Flash Gordons or Millennium Falcons vanquishing evil doers with laser blasts anytime in the near future. Perhaps we never will. As mind-blowing as it can be when human progress erodes the wall between science fiction and science fact, sometimes it is better that barriers remain. After all, a good writer might be able to construct a compelling narrative about a cat chasing a laser dot across the floor, but the story would probably lack the urgency made possible by the more lethal properties of fictional ray guns. And reality is probably better off without any more devices that make it easier for us to kill each other.

3 thoughts on “A Beam of Divine Light: The Story of the Laser”