Over the course of this series, I’ve spilled a lot of metaphorical ink exploring the origin stories of the monsters we celebrate this time of year. Most of these beasts were born long ago in the stories our ancestors told about dangers lurking in the dark forests that surrounded them and were preserved in our folklore. But we have driven many of these primal fears into the safety of our scary books and movies. I have never spent a lot of time worrying that the dead will rise from the grave and come for me or that a sorcerer will put a deadly curse on my family, but I sure do love stories about those sorts of things. On the other hand, I am agnostic as to whether there is life outside of our planet, especially the kind that is intelligent enough to develop the technology that would allow it to travel to Earth through interstellar space. The act of even pondering this question is in itself, a source of horror for me. I agree wholeheartedly with the great science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke who once opined that “two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.”

It might well be a transcendent occasion to discover that there are other entities in the universe who share our experience as sentient beings. Few of us are immune to the heartwarming sense of awe and wonder inspired by stories about first contact with benevolent extraterrestrials like those in E.T., Contact, or the 2016 masterpiece, Arrival. These movies are effective because they address that first type of fear, assuaging, if only temporarily, the feeling of existential loneliness by giving us a glimpse into what that interplanetary connection could be like. However, anyone who has seen more than a few horror and science fiction films is well aware that visitors from out of space are just as likely to be reptilian bipeds arriving in flying war machines, or mind-controlling slugs who slowly and secretly enslave the human race by melting our brains.

Besides their plausibility, aliens differ from vampires, werewolves, and witches, in one other important way. Those fiends of our ancient folklore arose in our dreams and fireside stories because they represented fears that are primal and universal, which is why there are eerily similar legends that exist across human societies. Every culture has historically believed in beings from other worlds, angels and demons, gods and demigods that sometimes breach our reality from some place outside of the human experience, usually a heavenly abode or dark underworld unreachable by human beings. But the idea of invaders from other planets is a very new phenomenon without a lot of precedent in traditional human lore. That is because until fairly recently, almost no one ever gave thought to the possibility that the bright objects floating in the night sky could possibly be in the same category as our own world and able to host life. As I’ll discuss in a bit, that little detail of reality is one that has only been widely accepted relatively recently in human history, and only after a long period of contentious debate.

It does seem worth asking though, if there are alien space explorers out there capable of visiting Earth, might there have also been such beings at earlier points in our history? And what would our ancestors, living before humanity had stumbled into the scientific processes that enabled us to begin mapping the cosmos, have thought about their strange visitors? Lacking the conceptual framework to accurately identify the aliens’ point of origin, they would have likely described their interstellar guests using the familiar concepts of deities and supernatural monsters that were available to them.

The famous astronomer Carl Sagan, applied this idea to the a race of demigods from the mythology of ancient Mesopotamia. Using a third century BCE history text written by a Chaldean priest named Berosus, Sagan asked the question of the Oannes, a group of human/fish hybrids who, according to Sumerian myth, emerged from the primordial sea that birthed all of creation to teach the first human beings the basic skills of civilization – writing, art, and science. Essentially, the Sumerians seemed to believe that they owed their cultural richness to a group of visitors from some other world who apparently arrived with very advanced technology. This mythic tale would make a solid modern sci-fi story about contact with extraterrestrials. As compelling an idea as this might be, I think it’s important to remember that Sagan also regularly touted that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and the admittedly eerie similarity between sagas of ancient gods and modern tales of alien races hardly qualifies as such.

Of course, intellectual rigor has not always been a firm obstacle for those wanting to sell interesting speculation as solid evidence. In the 1960s Swiss writer Erich von Däniken scoured the annals of myth and folklore in search of signs that our ancestors were visited by space beings. He provoked all sorts of controversy with the publication of Chariots of the Gods? in 1968, an essential work in the sprawling canon of pseudoscientific hokum. Von Däniken made bold claims that ancient architecture, the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, the monoliths of Easter Island, for example, could not have been built using the technologies of their day and must have been brought here by otherworldly intelligences. He also looked at comparative mythological concepts and assumed that people who were separated by time and space must have been connected via extraterrestrial intermediaries. The History Channel currently airs a program called Ancient Aliens that manages to earn strong ratings by continuing the work of von Däniken by combing the archives to find evidence that seemingly reveals the truth that ancient space travelers have visited our planet in the distant past. These narratives are admittedly compelling, in large part because they are both theoretically conceivable and unfalsifiable, but I urge us all to be skeptical of their claims.

For most of human history, people have been very cognizant of the objects in the sky and they built much of their understanding of reality based on the movements of planets and other celestial objects. But they didn’t have the tools to understand that they lived in a world that was analogous to the wandering planets in the sky. The ancient Greeks were the first to asking questions that led us to the counterintuitive reality of our universe that most of us now take for granted. A pre-Socratic philosopher form Ionia named Anaximander (c. 610-546 BCE) was the earliest human to reckon that the Earth was an object suspended in space. He was a little bit off in his contention that it was a cylinder-shaped column at the center of the universe, though. Later Greek thinkers like Democritus (c. 460-370 BCE) and Epicurus (341-270 BCE) posited that all matter was made up of an infinite number of atoms filling an endless void. This in turn gave rise to the conclusion that there must be an infinite number of worlds like ours which would logically be home to “alien” beings. They didn’t necessarily think these worlds were in the same physical universe as ours.

The Roman poet Lucretius was a follower of the Epicurean school of philosophy which is probably why he was the first person to speculate that the visible celestial bodies hosted intelligent life. He wrote in his most famous work, De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) in 50 BCE, that “in other parts of the universe there are other worlds inhabited by many different peoples and species of wild beasts.” A few centuries later, Lucian of Samosata (125-180 CE) a Syrian-based satirist wrote a story called The True History to lampoon the works of Herodotus and other ancient historians whose supposedly true accounts so often featured impossible journeys to fantastical lands. In Lucian’s tale, he serves as the narrator who is whisked away to the moon by a powerful storm. There he encounters lunar people flying around on giant birds and using strange hybrid plant and fungus weapons in their war against the ant-riding inhabitants of the sun over who gets to colonize Venus. Lucian was being very explicit however that these voyages were pure fiction, presumably by presenting the idea that alien races lived on other celestial objects as absolutely worthy of ridicule.

But these ideas were mere drops in the intellectual bucket of their time and with the rise of Christianity, they lost any currency they may have been poised to gain. Early philosophers of the new faith would hold close to the understanding of Plato and Aristotle who believed the Earth was at the center of the universe and was the one and only abode of life in the universe. These ideas fit well into the Christian doctrine that the world was created by God for man, one that did not leave lots of room for speculation about the existence of extraterrestrial life. There were a few Christian scholars who poked holes in the Aristotelian idea of a singular world. The medieval English theologian, William of Ockham (1287-1347 CE) noted that if God wanted to make other worlds he could, though most thinkers rejected the idea that he actually did. In his 1440 book On Learned Ignorance, the German cleric, Nicholas of Cusa pondered if there might be life on the moon, sun, and other heavenly bodies. He even went so far as to suggest that the other inhabitants of the universe could be superior to humans in some way. A few other thinkers got involved in such speculation, but the topic was not part of a vibrant society-wide conversation.

Historian Stephen Greenblatt argued eloquently in his book, The Swerve, that the rediscovery of Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things in a German monastery in 1412 was the singular most important event in launching the Renaissance that began the western world’s gradual move away from the shackles of religious dogmatism. Greenblatt’s argument is overstated on a lot of fronts, but that Lucretius’ book may have influenced the emergence of modern astronomy seems quite feasible. A century after its rediscovery, in 1512 the Polish mathematician, Nicolaus Copernicus published his theory that contrary to ancient wisdom, it was the Earth that revolved around the sun. Earth then was demoted from the center of the universe and was grouped in with the other planets as part of a solar system. To my knowledge Copernicus never publicly speculated on whether the other planets were home to life, but the fact that our own life-supporting world was now in the same category as our celestial neighbors made it inevitable that someone would ask this question.

The ideas he presented were controversial among other scholars, but not with church authority. In fact, Pope Clement VII was encouraging towards Copernicus’ work. This support would not last. For Protestants, of the time Copernicus was a heretic for making such claims, and the Catholic Church would eventually follow suit causing real problems for those who followed in his footsteps. The Dominican priest Giordano Bruno, took the ideas of Copernicus further, writing in 1584 that not only did the Earth revolve around the sun, but that the other planets “contain animals and inhabitants”. Moreover, he proclaimed that the universe had no center and that each star in the sky was itself a sun that was also orbited by planets that supported intelligent life. Although this was hardly the only issue that church authorities had with the controversial priest, Bruno’s views on the cosmos were heresies at the time and he was burned alive in 1600 by the Italian Inquisition. In 1610 Galileo avoided a similar fate by being more politically astute. After discovering Jupiter’s four largest moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Calisto – he received a letter of congratulations from the German astronomer Johannes Kepler who proclaimed “with the highest degree of probability that Jupiter is inhabited.” Galileo called the idea “false and damnable”. Whether he truly objected to Kepler’s assertion, or he was just being prudent remains an open question. Nonetheless, the new developments in science had brought the concept of extraterrestrial life into the human imagination.

By the end of the seventeenth century the culture was beginning to change. A French philosopher named Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle published Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds in 1686 written as a dialogue between two learned scholars in a conversational style that made it suitable for public consumption. The book ended up on the Church’s Index of Forbidden Books, but it didn’t get Fontenelle burned at the stake. In fact it was a best seller. The topics of discussion are essentially rooted in the ideas of Nicolai Copernicus and Giordano Bruno, but Fontenelle’s characters begin to wonder about the nature of the alien races that are taken for granted to exist throughout the stars and planets. At one point, his viewpoint character notes that if there are people on the moon, it is impossible for us to reach them, but does ask the pertinent question that would be at the heart of all alien invasion stories: ““What if they were skillful enough to navigate on the outer surface of our air, and from there, through their curiosity to see us, they angled for us like fish?

By the nineteenth century, most of the post-Copernican controversies had been settled. Virtually all educated people accepted it as fact that the cosmos was teeming with intelligent life. The only question remaining was, what were those people living on other worlds actually like? During this period several notable storytellers created fictional encounters to explore this line of inquiry. In his 1835 story “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” Edgar Allan Poe imagined a man who journeys to the moon in a hot air balloon who crashes into “a fantastical-looking city, and into the middle of a vast crowd of ugly little people”. Though he seems to learn a great deal of information about these lunar inhabitants, he withholds most of this information from his readers.

Camille Flammarion published Real and Imaginary Worlds in 1865, the first major science work to speculate about extraterrestrial life in light of Darwin’s recently published theory of natural selection. He hypothesized that sentient plants may thrive across the solar system. The red tint of Mars, he assumed was due to a particular type of flora that grew on its surface. Otherwise he believed that life was essentially like that of Earth, except for the fact that he thought “a race superior to our own is …very probable”. Flammarion was a widely popular science writer of his day, a sort of nineteenth century Carl Sagan or Neil deGrasse Tyson. His ideas were an obvious influence on the writers of scientific romances of the day like Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle. The rapid technological and social changes of the nineteenth century also prompted a many people to develop a deep interest in creating utopian communities. This is probably why places like Mars and Venus became popular settings in the speculative fiction of the day where writers could project their concepts of what a perfect civilization might look like onto other less corrupted worlds.

There was plenty of reason for readers of that era to want to escape into blissful alien societies. During the late nineteenth century, global tensions were brewing as the European power balance shifted and nations were using their industrial might to create deadly new armaments. This helped to inspire another popular genre of speculative fiction, the invasion novel. In 1871, British army general, Sir George Tomkyns Chesney anonymously published The Battle of Dorking in Blackwood’s Magazine. It was told as an account from the veteran of a fictional invasion of Britain by an unnamed German-speaking army who had already taken over Belgium and France. The Germans employ horrifying weapons and eventually go on to take control of the United Kingdom. The book was published on the heels of the Franco-Prussian War that ended earlier in the same year with the proclamation of a unified German empire. After the relative ease with which German armies had occupied France, Chesney took a good look at the state of the British army and trembled. He wrote the book as a piece of propaganda meant to spur the government into taking action in preparation for a war that became increasingly more likely as the century came to a close and the friction between European powers ratcheted up. It spawned several sequels and inspired a large wave of invasion literature like William Le Queux’s The Great War in England in 1897 (1894) and The Angel of the Revolution (1893) a book by George Griffith about a group of revolutionaries who harness the power of airships to conquer the world.

Scientific developments also seemingly made the existence of alien civilizations more certain. While observing Mars through his telescope in 1877, Italian astronomer, Giovanni Schiaparelli noticed a series of lines on the planet’s surface that he called “canali”. This word best translates into English as “channels” but many British and American newspapers reported that red planet was covered with “canals” which, unlike Schiaparelli’s chosen designation, suggested that these waterways were the result of deliberate engineering. Schiaparelli hadn’t intended to to make that claim, but Percival Lowell, an American businessman and amateur astronomer, picked up on this idea and ran with it. He studied the surface of Mars from his state-of-the-art telescope in Arizona where he too claimed to see long waterways so straight that he believed they could not have been formed through natural processes. According to Lowell, the trajectory of these canals – from Mars’ north pole to its Equator – suggested that a once-advanced civilization had fallen to ruin due to the growing aridity of the planet. In an effort to maintain their crumbling civilization, Lowell’s Martians redirected water from the polar ice caps to keep their crops growing. He wrote three books outlining his hypotheses and traveled far and wide lecturing on the topic. Though he divided the scientific world, his ideas provided a mental map of the red planet that would reverberate for decades to come in the growing body of space-based fiction.

In the slow acceptance of humanity’s place in the universe and wider questioning as to whether life existed beyond the planet’s borders, imaginative thinkers and storytellers had painted scenarios in which human beings by one means or another ventured out onto other planets, moons, or even stars. It wasn’t until 1892 when Robert Potter, an Irish clergyman published a novel called The Germ Growers about a race of alien beings who land in Australia and plan on destroying the human race with a deadly plague that anyone thought to imagine those alien people coming to Earth. Though it was arguably the first, Potter’s book hardly jumps to the front of anyone’s list of great alien invasion stories. Another novel that would be published later in the decade, though, would become the single most important event in the development of the modern horror icon that is the monster from outer space.

Most of the Halloween monsters I’ve covered over the years have roots in different folklore traditions. A few of these became fictional tropes with the creation of a distinct and iconic piece of fiction. Bram’s Stoker’s novel, Dracula for example, became the archetypal vampire story and the 1968 George Romero film, Night of the Living Dead virtually created the modern undead zombie. Perhaps even more than any of those works, the singular event that gave us the ubiquitous trope of the hostile alien invader, was H.G. Well’s seminal 1897 novel, War of the Worlds. The British author was on quite a tear with the success of The Time Machine (1895) and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) by the time he started writing his alien invasion tale. Wells drew on multiple thought strands that were prominent at the close of the nineteenth century. He was inspired by the interplanetary themes in the scientific romances of his day, many of which used alien civilizations as analogs to explore the problems in our own societies or to imagine how they could be better. The Martians in the book were forced to act out of a major crisis on their planet that was predicated on the “canal builder” theory of the Red Planet touted by Percival Lowell and others. But the most important innovation he brought to the proto-science fiction genre of his time, was making the choice to depict extraterrestrials in the literary style of the invasion novels discussed above.

He certainly played into the global anxieties that made invasion literature so popular during that time, but where the bulk of those stories were decidedly nationalist in tone, Wells chose to re-center his criticism. A socialist and a staunch critic of British imperialism, Wells aimed his sights not at his country’s military preparedness, but at its unjust treatment of colonized peoples. He was particularly horrified by the massacres and displacement of populations whose levels of technology would made them highly vulnerable European weaponry. Wells was appalled by the effects of artillery bombardment by the British navy upon nomadic people they encountered. He notes in the preamble of the book that:

…ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years.

War of the Worlds was written, in part, as a thought experiment about what might happen if one of those advance European civilizations ran into an alien military force armed with flying machines and death rays. He clearly wasn’t optimistic.

Unlike most of the popular scientific romances of the late 1800s that focused mainly on the socio-political aspects of the aliens they depicted, Wells was interested in exploring biological questions. In particular, he was interested in how Darwinian evolution would proceed in a vastly different environment than any found on Earth. As a result, he created the octopoid Martians who were utterly inhuman in appearance. We get very little of their views outside of their apparent will to commit genocide in order to take control of our planet. We know they come from a dying planet that is rapidly running out of resources, so rather than being a horde of evil monsters, the Martians are simply practicing the social Darwinist imperative of survival of the fittest that nineteenth century elites used to justify the gross inequities rampant at the time. But it is ultimately, their biology that would be the Martians’ undoing. Humans prove technologically unable to halt the process of these invaders through military means, but because they arrived on a planet teeming with microscopic life that their alien immune systemes had never encountered, the Martians easily succumb to a common cold.

Wells’ alien invaders also employed the sort of advanced technology that would help to terrify horror and sci-fi fans for the next century and more. They come in giant space-faring cylinders and attack with flying ships and the nightmarish tripod “fighting machines” that allow them to trample all over London and reduce British armies to smoldering ruins with powerful heat rays. These weapons were one of the earliest examples of alien energy beams that would inpire the laser gun that is so ubiquitous in modern science fiction. From slugs and shape shifting-slime molds, arachnid-like giants, and xenomorphs, the alien monsters that have filled our books and movies for more than a century are the children of H.G. Wells.

The deadly technology wielded by the Martians in War of the Worlds underscores another reason that the alien invader is such a new edition to the monster canon. Before the nineteenth century, industrialized warfare was simply not a part of the human imagination. Once human ingenuity began to spur an incredible arms race in killing technology, the anxiety of what a modern war would look like became embedded in the Earth’s population. This fear would begin to be tragically realized in the summer of 1914 with the commencement of the First World War that showed humanity the horrible potential of tanks, massive artillery, aircraft, poison gas, and other monstrosities enabled by modern industry. It was in the years after the war that horror cinema would come into its own, from the German expressionist nightmares like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu in the 1920s to the Universal Gothics like Dracula and Frankenstein in the following decade. Those years also gave rise the genre of science fiction that remains a close cousin of horror. The space monsters that frequented sci-fi stories, armed as they always were with incredibly powerful technology, quickly became the stand-in for foreign armies with increasingly destructive armaments.

The origins of sci-fi is a fraught topic, though unquestionably many of its most fundamental tropes – journeys into space, future worlds, time travel, and robots -were products of the exponential increase in technological development during the prior century and the scientific romances of authors like Wells and Jules Verne. But it was a publisher of a pulp magazine called Amazing Stories named Hugo Gernsback that gave the genre its name in 1926. From the beginning, aliens made frequent appearances in Amazing and other in pulps of the period but they usually behaved more like bad guys in adventure tales there only to be defeated by heroic protagonists than the monsters of the Universal movies who were meant to scare audiences. The sci-fi pulps took a decidedly techno-optimistic approach with heroic galactic adventures like E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark and Lensmen series.

There were a few notable exceptions. The first issue of Amazing Stories published in March, 1926, featured a story called “The Thing from—’Outside’” by George Allan England, a very strange tale that was possibly the first to imagine that in the eyes of a super intelligent alien race, humanity would be mere guinea pigs for experimentation. In September 1931 Amazing published another rare invasion tale, “The Arrhenius Horror” written by a chemist named P. Schuyler Miller who imagined a visitation by a hostile alien entity in a remote part of Africa by silicon-based spores that merge into a giant sentient crystal with ill intent for humanity.

Mainly, though the alien invasion stories that carried the DNA of War of the Worlds into the horror genre going forward appeared in the pages of the dark fantasy magazine, Weird Tales. Though long since forgotten, two stories published in 1925 were very popular examples that helped established extraterrestrials as a firm trope in the horror genre. J Schlossel’s, “Invaders from Outside” (January, 1925) was a clever yarn about an invasion of the solar system by a giant extrasolar planet that wipes out a string of civilizations stretching from the moons of Uranus to Mars and forcing a few refugees to land on Earth long before the evolution of humanity. The ending implies that our species origins are extraterrestrial, a trope that inspired not just many stories to come, but also a scientific hypothesis that is still debated today. Nictzin Dyalhis’s “When the Green Star Waned” (April 1925) features an expedition sent from Venus to protect the primitive people of Earth from a hostile alien invasion party.

In the 1920s pulp writing star, Edgar Rice Burroughs looked to emulate some of the pre-World War I invasion stories by conceiving of a tale of a future United States taken over by Soviet Bolsheviks. Publishers rejected the premise so Burroughs did what so many writers to come would do and turned his evil humans into extraterrestrial invaders. The 1926 book The Moon Maid about a future, near Utopian world (enforced by joint American and British military force) begins space travel only to invite the wrath of lunar monsters who come to Earth and destroy human civilization.

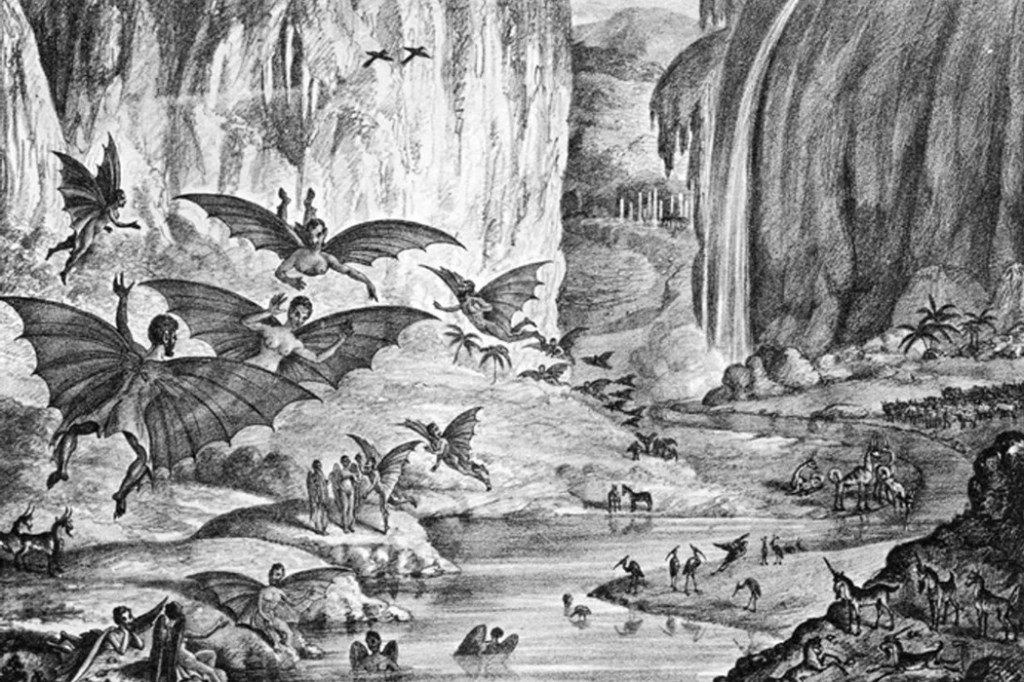

Another author who toiled away in obscurity during the interwar period would come to have a profound impact on the future of how extraterrestrial entities would be presented in the latter half of the twentieth century and beyond. H.P. Lovecraft’s stories are not usually classified as science fiction, rather he is widely considered the single most important bridge between pre-twentieth century Gothic fiction and modern horror. He was greatly influenced by Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen, M. R. James and other nineteenth century authors whose horrors were usually quite terrestrial in their themes, touching on dark topics like ancient witchcraft, human sacrifice, and sinister rituals that rang of Satanic or secret pagan rites. On the surface, Lovecraft’s stories were very similar. “The Festival” published in Weird Tales in 1925 is about a cult of worshippers who summon a host of demonic entities in a secret catacomb during Christmas vacation. “The Dunwich Horror” (1928) features a family in rural New England who sire a pair of abominable children by commencing esoteric rituals to the god, Yog-Sogoth. His 1933 short, “The Dreams in the Witch House” tells of a student who rents a room that is haunted by the spirit of a black magician who escaped the authorities during the 1692 Salem witch trials.

Lovecraft did write some tales that are explicitly about human contact with some truly alien entities. In “The Colour of Outer Space” written in 1927, a meteor lands in rural New England and poisons the groundwater with a sentient “color” that kills crops and livestock and drives the locals to madness. His 1930 tale “The Whisperer in Darkness” is a bit more conventional, but its fungoid extraterrestrials who are able to remove human brains and put them into canisters for space travel were certainly novel for the time. But most of these stories, including the occult-themed tales of elder gods were told on top of a vast mythos that stretched deep into outer space. This is made clear in his 1936 novella, At the Mountains of Madness, about an Antarctic expedition that discovers an ancient alien city, built billions of years earlier that would eventually go on to inspire many of the secretive black magic rites that existed secretly throughout human history. Essentially, all of those bloodthirsty deities worshipped by atavistic pagan fanatics were a race of ancient space monsters.

In War of the Worlds, H.G. Wells was using his Martian invaders as a comment on the barbaric ways imperialist cultures viewed their colonized subjects. Lovecraft’s aliens related to the entire human race as a god might to a gnat. The horror of these entities is not so much that they plan to conquer humanity, replace us with mindless replicants, or even use our flesh as food. They are entirely indifferent to us, but their immense power is all around and has penetrated the dreams of ancient humans causing them to invent every god and religion we’ve ever conceived. The danger lies then in the ways they inadvertently inspire humans to commit horrific acts in their name. For individuals who learn the truth about this esoteric cosmic order, the ultimate danger is that our minds cannot comprehend their existence without sinking into utter madness, which is, in fact, the fate of many of Lovecraft’s protagonists.

His most famous story, “The Call of Cthulhu” is perhaps the most indicative of the cosmic terror that enveloped the Earth. It posits that through a series of seemingly unrelated accounts of an ancient archaeological sculpture, shared nightmares between a dispersed group of artists, a police report about an urban cult, and a strange encounter at sea, a scholarly investigator begins to piece together the fact that Earth lies at the mercy of the powerful extraterrestrial entity called Cthulhu that sleeps deep beneath the ocean. The narrator begins to see that the terrible events occurring across the globe are inspired unknowingly by the dreams of that sleeping alien. Even more terrifying though, is that when the ancient one awakens, the end of the world will follow swiftly.

Unfortunately, Lovecraft’s ability to so effectively portray horrid alien beings was surely rooted in his own fear of difference that inspired incredibly bigoted views towards anyone of non Anglo-Saxon origin. He would neither be the first nor the last writer of fiction to use menacing creatures from outer space as stand-ins for outside groups they hated or feared. Yet he was also terrified by the great scientific developments of his age that improved our understanding of the cosmos and increasingly made our once privileged place in our imaginations untenable. One doesn’t need to be a racist or xenophobe to experience the sense of overwhelming terror at the thought that we live at the mercy of a cold and unfathomable universe, and giving voice to this fear has been Lovecraft’s most lasting legacy. Over the last few decades the term cosmic horror has come into vogue to describe stories where the evil is rooted in incomprehensively alien forces from outer space or some other dimension. In our modern world where vampires and mummies seem to lack the ability to horrify us like they did previous generations, the concept of monstrous entities of such sublime power from us still seems to resonate with our most intimate fears. I’ll touch on this theme a little bit more below, but this is a very large topic that will show up again in some other October post of its very own.

British philosopher, Olaf Stapleton had a similar sense of human insignificance in the face of the gaping endless cosmos, but unlike Lovecraft, he met this with a sense of wonder rather than horror. Still he could spin a pretty creepy alien invasion. He set out to write a treatise on the human condition rather than a Sci-Fi story in his 1930 billion-year spanning future history Last and First Men. A section of the novel outlines an invasion by a cleverly conceived race of microscopic entities from Mars who come to Earth because their own planet is suffering from a terrible drought, an idea no doubt borrowed from the theories of Percival Lowell discussed above. The aliens are smaller than Earth viruses but able to group into larger, more complex units that appear to human eyes to form a large green cloud. They use electromagnetic energy as a communication medium in lieu of spoken language. This leads them to believe that Earth’s radio stations are sentient beings and human beings are their machine-like servants. After a long struggle lasting 350,000 years, they are wiped out by an advanced human-engineered biological weapon.

One of the most creepy and enduring tales of interstellar menace from the interwar years was John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella “Who Goes There?“. The story takes place in an Antarctic research station where a team of scientists and engineers discovers a twenty-million-year-old space craft. The ship is occupied by a block of ice frozen around the ship’s former pilot. As you have probably guessed, they thaw it out and very bad things begin to happen. It turns out, the creature can assume the form and memories of any living thing it encounters. Soon one of their own, a physicist named Connant, is killed and replaced by the entity. It then begins to imitate other members of the team as well as their sled dogs, and soon no one can no for sure who is human and what might be an alien doppelganger. The alien’s covert nature sets up a mood of ever-present fear and extreme paranoia that would play well in the tense political climate of its time, particularly coming from Campbell whose reactionary anti-communism made him the perfect mouthpiece for using extraterrestrial science fiction to create nationalist and xenophobic propaganda. Given the year it came out, one didn’t need to be a rightwing zealot of Campbell’s stripe to feel anxious about the global situation.

A few months after Campbell published “…Who Goes There?” a seminal event proved just how effective of a monster the extraterrestrial had become for addressing modern anxieties in the few decades since The War of the Worlds was published. In fact, it was an updated adaptation of that story served as a the catalyst for a low level panic that struck the populace. On October 30, 1938, radio ingenue Orson Welles broadcast a rendition of H.G. Well’s novel. on his CBS show, Mercury Theater on the Air. Rather than a straight-forward re-telling of the story in a radio play format, Welles drew upon his childhood memories of playing Halloween pranks on his neighbors, with hopes having a little bit of mischievous fun with his audience’s expectations. It worked. He changed the setting of the Martian landing from Britain to rural New Jersey and much of the action takes place outside of metro New York where the bulk of the program’s listeners were based. The second half of the show was straight narrative, drawn largely from the pages of the book, but for the first half hour, listeners who tuned in would have heard what sounded like a leisurely musical performance abruptly being interrupted by a breaking news report that an unusual object from outer space was hurtling towards Earth. The updates became increasingly more alarming culminating in a harrowing on the ground report of the Tri-State area being conquered by tentacled space monsters armed with devastating death rays.

The broadcast’s aftermath has been subject to a fair amount of mythologizing, some of which was strongly encouraged by the consummate showman that was Orson Welles. I grew up believing the conventional wisdom that the infamous War of the Worlds broadcast caused a state of mass panic across the country. More recent historical looks at news coverage in the following days show that this narrative is a bit overblown, but post broadcast reports make it clear that it wasn’t a non-event either. Some listeners were clearly spooked by the show and evacuated their homes and the FCC did investigate Orson Welles and CBS radio. And it makes sense that the story would have freaked its audience out. Adolph Hitler’s recent rise to power and German invasions of Austria and Czechoslovakia earlier that year made it seem inevitable that another world conflict was on the horizon. Moreover, newer, more fearsome weapons were had ben devised since the First World War. The Spanish Civil War (1936-39) had been a testing ground for aerial warfare to deadly affect and for Americans who had long felt protected by two the large oceans that had always separated them from aggressors on the other sides of the globe, the world seemed to shrink. Can you blame anyone under these circumstances for for responding in a very primal way to the threat of monsters coming down from the skies?

The same belligerents who had waged the Great War were about to embark on another conflict that – like every effective horror sequel – was reminiscent of the original, but bigger and more intense. World War II ended with the use of the most powerful weapon human beings had ever seen and it changed everything. If World War I world left people depressed over the meaninglessness of all of the mechanized death and destruction it had wrought, its follow-up left the population of Earth in a cloud of existential dread at the realization that our species now had the power to wipe itself off the Earth with the push of a few buttons. This low-grade terror simmered to a boil in 1949 when the United States’ new global enemy, the Soviet Union, detonated its own weapon of mass destruction. Two antagonists now pointed missiles at each other that made the heat rays employed by H.G. Wells’ Martian invaders at the end of the nineteenth century look mild in comparison.

The resulting Cold War was a strange time culturally for Americans. On one hand, they’d helped to defeat the fascist threat and come out of the battle unscathed, relative to the damage done in Europe and around the rest of the globe. Many of the technologies developed during wartime now shifted over to commercial applications and created a brand new sense of innovation and a sense of great optimism about the future. It was a time that saw the birth of a youth culture of rock and roll, TV shows, and drive-in burger joints that would spread worldwide – a golden age that American conservatives still point to as an example when looking to make their country great again. Yet all of this blossomed in the shadow of the atomic menace that hung over the heads of every man, woman and child on the globe.

One of the ways that underlying tensions always leak through illusory cultural stability is through horror fiction, and Cold War anxieties found their way to cinema screens across America. The old Universal Studios horror formula of Gothic monsters in old castles and foggy moors had gone out of vogue after the war, and the gritty realism of film noir seemed to dominate in its place for awhile. But with the success of the George Pal-produced science fiction blockbuster, Destination Moon in 1950, American movie goers seemed ready to enter the world of brightly lit escape to the stars. But what followed in the next decade or so was the kind of escapism that could only flourish in the Atomic Age. Many of the sci-fi monsters of the 1950s silver screen- unusually large ants, miniature humans, and giant undersea reptiles, to name a few – were the products of radioactive accidents. You couldn’t get more on the nose than that. But the fear of a malicious and powerful foe armed with potentially life-ending weaponry and the US government’s response to that threat, were most effectively dramatized on film by a new swath of extraterrestrial visitors. The year after Destination Moon wowed audiences, two iconic American alien invasion movies hit the screen with very different messages.

Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still is an all-time masterpiece of a science fiction film that fit perfectly into the age of dread and optimism that was the 1950s. It’s premise was simple, and simultaneously horrifying and uplifting. A ship lands in Washington D.C. carrying two alien visitors; a humanoid named Klaatu, and his giant robotic sidekick Gort. Klaatu brings a message of intergalactic peace and unity that is certainly touching, yet it is embedded with a threat that, should the nations of the world pursue their current course of nuclear armament, an alien federation will be forced to destroy the planet in order to protect galactic stability. Klaatu is a mostly benign figure (despite the ultimatum he has come to deliver) he wishes to learn about the cultural and artistic achievements of the human species, and ultimately steer the inhabitants of our planet in a more prosperous direction. Gort, however, is an indestructible space monster capable of emitting an energy beam that instantly vaporizes the most advanced human weaponry. His menacing, metallic appearance would influence lots of films to follow.

Another iconic movie of the era hit the screens that same year with a much different message than The Day the Earth Stood Still. The former had all the hallmarks of a sci-fi horror of its time, but it was embedded with a not-so subtle anti-war message that angered many in the military establishment. The Thing from Another World stood in sharp contrast. An adaptation of John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella, “Who Goes There?” it was a straight up horror and far more black and white in its moral stance. Christian Nyby is credited as the movie’s director, though many contend it was actually directed by the film’s screenwriter and producer, the staunch conservative, Howard Hawks. The source material’s story about a space monster who invades an Antarctic research base was changed a bit to adapt it to film. The monster was turned into a giant humanoid as the shape-shifting creature in Campbell’s novella was not practical given the special effects of that time. The setting changed from a research station in Antarctica to a military base in Alaska, close to the border with the Soviet Union in order to capture the geopolitical tensions of the day. Nonetheless, the film maintains the stark paranoia of Campbell’s story, though, and is unabashed in its contention that the enemy should be met with force and defeated by a heroic force of US servicemen.

Existing somewhere in the murky middle between these two poles was Don Siegal’s 1957 thriller, The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Based on a 1954 novel by Jack Finney, the story takes place in a small California community where some of its citizens begin to notice that their friends, family, and neighbors have been acting very strangely in recent days. The tension simmers until a doctor named Miles Bennell, his girlfriend Becky, and a small group of trusted locals discover that a host of alien seed pods have landed in town. When these horrifying looking cocoons hatch, exact replicas of their neighbors, formed while they sleep, emerge ready to commence the takeover of Earth. The film’s masterful level of suspense and paranoia have led critics to argue about its underlying political message. For many, the alien invasion is an allegory for the secret communist infiltration of the United States, a fear exacerbated by a series of high-profile cases earlier in the decade that revealed several figures with high-ranking government clearances had been Soviet spies. Others saw the movie as a critique of the authoritarian policies undertaken by the government that culminated in the McCarthy hearings and the unfair blacklisting of alleged subversives in the entertainment industry. Still others saw in the movie, an attack on the vapid cultural conformity of the Eisenhower era. Finney, director Don Siegal, and the film’s lead actor Kevin McCarthy, have all stated that the story was meant only as escapist entertainment, but the film has endured because its tone unquestionably played on the various tensions that hung around in late 1950s America.

Most of the sci-fi B-movies of the mid-twentieth century had no overt political messages, but their formulaic defense of the status quo was contained deeply conservative connotations that cultural critic Susan Sontag called “haunting and depressing”. The basic idea of the goodness of the human (i.e. western capitalist) armies against the alien otherness that represented the evil of communism was always lurking in the background context of American movies. In the 1953 George Pal produced War of the Worlds was clearly a piece of escapist cinema, but its anchor in religious faith (in strong contrast to Wells’ source material) undoubtedly signaled to audiences the superiority of US military and cultural might to that of the “godless commies”. Invaders from Mars (1953) similarly called upon US military bravery to stop a secret invasion of a small town in middle America. Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956) was perhaps the most simplistic big budget invasion film of the time, though it was a hit with moviegoers who undoubtedly came to watch the destruction of major Earth landmarks by the evil alien saucers.

Whatever their underlying politics, this wave of popcorn films helped give birth to a teenage culture that sought to display fun frights and not a lecture overtly or covertly on geopolitics. The 1958 Steve McQueen classic, The Blob about a protean mass that eats everything it touches was delivered with a hip rock and roll soundtrack that made it a huge hit. I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) was similar to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and is a fairly tense movie, but it brought the invader into the living room. The alien husband is part of a race of extraterrestrials who has come to Earth to take our women. There is a lot of social commentary to read into the film, particularly in regards to 1950s domesticity, but for most viewers, it was a simple thriller. Roger Corman’s Not of this Earth was perhaps as apolitical of a Cold War-era invasion movie that it was possible to make. It showed aliens coming here for our blood thus drawing on old vampire tropes for a new audience. Ed Wood’s 1957 cult classic Plan 9 from Out of Space did briefly feature the most legendary celluloid vampire of the day. Bela Lugosi was to be the star of the film about an alien plan to raise the dead on Earth and turn then into a conquering army. Sadly, he died before the film was completed which is why there is a guy who vaguely resembles Lugosi wandering around with his face covered by a vampire cloak for most of the movie.

There were a few monster movies of the era that snuck a little more nuance into their narratives. It Came from Outer Space (1953) was a bit more heartfelt than the average B-movie of the decade, no doubt because it was based on a Ray Bradbury script depicting aliens who crash land in the Arizona desert, not to invade the planet, but by sheer accident. The 1957 20 Million Miles to Earth similarly avoided the black and white morality of other atomic age invasion stories by including a creature designed by FX wiz, Ray Harryhausen, who engenders a bit of sympathy, though not enough to keep him from being obliterated by Uncle Sam.

The 1950s was also the opening of the Space Age. With the launch of Sputnik on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union had put the first human-built object into orbit. This was a source of great anxiety in the U.S., where the fear of future communist space weapons mingled with the humiliation of knowing the Reds got there before us. This was only heightened on April 12, 1961 when the USSR launched Yuri Gagarin into space, making him the first human to leave the Earth’s atmosphere. Suddenly, the idea of launching rocket ships into space to explore other worlds was no longer the stuff of 1920s pulp science fiction stories

Movies about humans encountering hostile extraterrestrials in space became as popular as those showing them coming to us on our home planet. This was not a new idea in cinema. The first science fiction film ever made, Georges Méliès 1902 short, “A Trip to the Moon” was exactly that type of story. But in the 1950s there was a wave of films featuring brave human explorers taking to the stars, only to find other worlds populated by dangerous monsters. In the 1958 classic, It! The Terror from Beyond Space a returning mission from Mars finds their ship has a stowaway, an alien monster from the Red Planet. What ensues is eerily similar to an iconic 1979 Ridley Scott film that I’ll discuss below. In the UK, Hammer Films would spearhead a return to Gothic storytelling with its Dracula and Frankenstein franchises beginning in the late ’50s. But it would start its amazing run in 1955 with The Quatermass Xperiment, a sci-fi thriller about a rocket returning to Earth after the first successful manned launch, only to discover that there is something not quite human about the only survivor of the mission. Forbidden Planet was a sophisticated take on the science fiction genre and a pioneering space opera film. Loosely based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the story involves a crew of space explorers who arrive on the planet Altair IV where the one scientist who remains from an earlier expedition is haunted by the powerful technology of an extinct race of aliens.

During this period a powerful new entertainment medium emerged that would bring aliens to people’s living rooms. In 1950, fewer than ten percent of homes had television sets, but by the end of the decade more than ninety percent did. Promising new writers spilled into the newly emerging TV industry hoping to tell stories that would meet a wider audience than was possible in the cinemas. But the stories they could tell became subject to the lowest common denominator due to the influence of gun-shy sponsors unwilling to put resources behind controversial material for fear of offending large segments of the viewing audience. Rod Serling, was an upcoming star in the world of television writing and he would find himself running afoul of this system, time and time again. He believed that the writer must “see the arts as a vehicle of social criticism and he must focus the issues of his time.” Unfortunately, the sponsors usually didn’t agree. Serling was horrified by the 1955 murder of a young black child named Emmett Till and the unjust acquittal of his killers by an all-white jury in Mississippi. He wrote a teleplay about the story in order to show the country the dark underbelly of racism that haunted it, but sponsors (including Atlanta based Coca Cola) who feared angering Southern audiences pushed for changes to the script until it became an unrecognizable shadow of Serling’s original idea. In frustration he turned to science fiction as a way to critique society without turning off the sponsors. As we have seen, extraterrestrials were an effective metaphor for all sorts of conservative bugbears, but Serling found ways to use them to tell more progressive stories. As a result, he launched the anthology series, The Twilight Zone in 1959. In one of the most poignant episodes in the show’s five-year run, “The Monsters are Due on Maples Street” alien invaders come to Middle America, armed not with deadly anatomical features or super-powered weapons, but rather the ability to fidget with the electricity on a suburban American neighborhood. It turns out, that this little trick is just enough to make fear an paranoia turn regular people into a dangerous mob. Serling also gave us lots of less political but clever twists on the idea of alien invaders. The culinary spin in “To Serve Man” or the trope-subverting ending of “The Invaders” all helped to push the genre in a new direction.

The 1950s also saw the transition of science fiction written word move from pulp magazines to viable novels. Robert Heinlein, a Cold Warrior at heart wrote The Puppet Masters about a species of extraterrestrial slugs that are a blatant metaphor for Soviets. Even more militaristic was his story of arachnid monsters coming from space to destroy the planet in Starship Troopers (1959). Arthur C. Clarke was more critical of the Cold War policies of the US and its allies, and his 1953 novel Childhood’s End took a more subtle approach to the concept of an extraterrestrial invasion. Clarke’s alien “Overlords” come peacefully and share their technologies with the human race creating a Utopian world, but one that comes at the cost of the individual identity of everyone on Earth. In some ways it mirrored the geopolitical debate between communism and capitalism but its haunting conclusion leaves readers with no clear answers.

It’s easy to inject these fictional stories with analyses of Cold War anxieties and unease about new technologies, but they also reflected very tactile fears that were beginning to arise in the post-war years. It’s hard to say what caused the UFO boom during this time, whether it was the result of living under the shadow of the atomic bomb, or the boredom that domestic tranquility seems to inspire, but lots of people began seeing alien space craft in the sky in the late 1940s.

Speculation about alien visitations have been around for some time. Throughout the later half of the nineteenth century technological progress was moving at a rapid rate and the first airships began to soar across the sky. The century’s final decade also coincided with Percival Lowell’s public campaign to prove that Mars hosted an advanced civilization. All of this perhaps helps to explain a string of strange sightings in 1896-97 that were frequently attributed to extraterrestrial visitations. Most of these accounts came from witnesses who saw strange lights or unusual shapes in the sky. The most dramatic came from Colonel H.G. Shaw in Stockton, California, who claimed to have come across three seven-foot tall beings on November 19, 1896. According to Shaw, the visitors slightly resembled humans but were “covered with a natural growth hard to describe. It was not hair, neither was it like feathers, but it was as soft as silk to the touch,” and who he further described as having “faces and heads …without hair, the ears were very small, and the nose had the appearance of polished ivory,” Shaw said. They had tiny mouths, “while the eyes were large and lustrous.” Shaw claimed the creatures tried to abduct him and put him into a craft that hovered nearby, but they did not possess the strength to force he and his companion into their ship. He speculated to the Stockton newspaper those we beheld were inhabitants of Mars, “who have been sent to the Earth for the purpose of securing one of its inhabitants.” Shaw became the first public figure associated with extraterrestrial contact. He wasn’t the last.

During the Second World War fighter pilots in multiple theaters claimed to see strange objects flying around them. These experiences became so common that American pilots gave them the name “foo fighters” based on the nonsense alliterative word “foo” that appeared frequently in the comic strips of the 1930s. After the war, these types of aircraft seemed to visit with even greater frequency. On June 24, 1947 a civilian aviator named Kenneth Arnold claimed so spot from his airplane nine flying objects moving very fast in an organized formation over Mount Rainier in Washington. He described them as “saucer-shaped”. His report would become a media sensation and as a result of his vivid description, the idea of the “flying saucer” joined the popular lexicon. A few weeks before that a quieter incident occurred that would prove to have a lasting impact on the discussion of alien visitors to Earth.

On June 14, 1947 W.W. “Mac” Brazel and his son Vernon were driving across their property in the area north of Roswell, New Mexico when they came across a pile of wreckage that looked otherworldly to them. They brought the strange materials to the sheriff, George Wilcox who was equally freaked out by what appeared to him to be the rubbery, metallic remains of some kind of aerial craft. The sheriff called the local Air Force base, and the story made it up the chain of command. By the time military officials commented on the discovery, rumors of UFOs were spreading widely across the area and into local news reports. At that time, the Air Force actually preferred the public believed the rumor about a crashed flying saucer, than it discover the real top secret purpose of the downed aircraft. The “UFO” that Brazel and his son came across had been a government weather balloon equipped with specialized listening equipment set to fly over the Soviet Union as part of the top secret program, Project Mogul. Its mission was to monitor the atmosphere in order to detect whether the Soviets were testing atomic weapons. Given the paranoia running rampant immediately after the defeat of Nazi Germany and the emerging conflict with the USSR, the government’s secretiveness became a sure sign to many people that it was hiding aliens outside of Roswell. A large testing and training area in Nevada, surrounded by ominous signs warning trespassers that they would be met with deadly force, would become part of the modern folklore of alien visitation to Earth. That facility is known as Area 51 and there are many who still claim unequivocally that this location is the military’s hiding place for a collection of alien spacecraft and the remains of their extraterrestrial pilots.

By the end of 1947, sightings of UFOs became so widespread throughout the media that policymakers began to wonder what was really going on. The United States government opened Project Sign, the first of a series of officially-sanctioned studies to try to get to the bottom of this strange phenomena. In 1952, Project Blue Book was established to determine whether any of these reports pointed to issues that posed an actual threat to national security, or perhaps could produce usable scientific breakthroughs. For nearly two decades Blue Book collected data under a revolving door of leadership with different views on the issue and conflicting approaches to how to approach the UFO question. In 1966 the Condon Committee was formed to analyze the data gathered by these studies and after two years it released a report that was nearly fifteen thousand pages long and concluded that, “on the basis of present knowledge the least likely explanation of UFOs is the hypothesis of extraterrestrial visitations by intelligent beings”. Project Blue Book was terminated soon thereafter. Nonetheless, the question of whether Earth was being visited by aliens remained open for many in the public.

In fact, accounts of extraterrestrial invaders became more spectacular. The Betty and Barney Hill abduction case of 1961 was the most controversial to date and remains a central piece of the UFO narrative to this day. In September of that year, the couple were driving through the White Mountains of New Hampshire when they saw a strange light in the sky. Initially they waved it off as a shooting star or airplane, but when they realized it seemed to be following them, they stopped the car and watched as it came closer. As the object arrived it was clear that the Hills were looking at some sort of advanced aircraft and Barney could see inside its windows where a group of gray-skinned beings with large eyes and unusually-shaped heads closely observed he and his wife. The craft quickly disappeared and the Hills resumed their journey home. That’s when things really got weird.

Over the next few days Betty and Barney noticed a series of bizarre things. Their watches had stopped working. The clothing they had worn during the encounter, and some of the items they’d been carrying were inexplicably torn and worn down as if they’d been through a rugged experience. Moreover, for reasons they couldn’t understand, their drive that had taken four hours had actually lasted seven, and they could not account for the lost three hours. Betty soon began having dreams about the experience in which she and Barney were taken into the nearby woods under some form of mind control by a group of strange gray men. After attempting hypnotic memory recovery, both started to remember things about that night, accounts that matched up with Betty’s dreams. Soon their story became the subject of books, movies, and a template for other more detailed accounts of people who who made even more elaborate abduction claims. Their descriptions of the extraterrestrial visitors also popularized the “gray alien” archetype that has become so prevalent today.

By the mid-1960s alien invasion movies had begun to go out of vogue with the success of thrillers like Psycho, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, and Repulsion, and the Gothic revival prompted by the work of Hammer Studios and Roger Corman’s Poe Cycle. The relaxing of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1966 began to push horror films in more graphic, grim, and realistic directions.

The nihilistic filmmaking of the late 1960s and ’70s, and the gritty new generation of horror that it birthed eventually began to explore sci-fi concepts again. However, the Cold War consensus of the 1950s commie-coded space monsters of that era no longer resonated with audiences. Most of the science fiction films of the decade depicted very human villains with powerful technologies that often led to grim dystopian futures in stories like Soylent Green, A Clockwork Orange, and George Lucas’ pre-Star Wars nightmare, THX-1138. There were a few exceptions, though like The Andromeda Strain, Michael Crichton’s story of an alien microbe that threatens to end all life on Earth and the 1978 Philip Kaufman remake of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The newer version eschewed any Cold War politics in favor the post-Vietnam and Watergate paranoia and distrust of the authorities with a much bleaker outcome than its predecessor.

Few films that never got made have received the same level of attention as Alejandro Jodorowsky’s planned adaptation of the 1965 Frank Herbert novel, Dune. The primary reason for its fame was that in the summer of 1975, the avant-garde Chilean director gathered a group of talented individuals in Paris for a very expensive pre-production process that likely sank the movie before the cameras began to roll. It has become legendary how that artistic team’s conceptual work went on to influence such sci-fi heavy hitters to come as Star Wars, Blade Runner, and Terminator. But no film more directly emerged from that brief collaboration than the 1979, Ridley Scott horror sci-fi, Alien.

Alien‘s screenwriter, Dan O’Bannon had served as the special effects supervisor for Dune. After the project ended, he came home and decided to dust off an old idea of his to make a haunted house movie set inside a spaceship with a small number of astronauts, a sort of science fiction version of The Haunting. No studio seemed very interested in the idea until the success of Star Wars in 1977 drew in up-and-coming director, Ridley Scott. The movie was not all that complex. It was basically a well-shot B-film in the vein of 50s sci-fi popcorn flicks, but it added some interesting elements that made it an all time classic. The seasoned cast of actors that included John Hurt, Tom Skerritt and Harry Dean Stanton was headed by Sigourney Weaver who played Ellen Ripley, a tough female protagonist in an era when such a thing was still rare. The working class vibe of the film gave a relatability not common in sci-fi films that had traditionally been led by gallant heroes and brilliant scientists. And above all, there was the design of the alien Xenomorph. The creature was conceived by Swiss artist H.R. Giger whom O’Bannon had met during the pre-production of Dune. Giger thought deeply about the monster’s appearance, sketching it with elements of humanity’s most primal fears. He mixed reptilian and insectoid features with some very sharp teeth, claws, and stingers and threw in acidic blood for good measure. This along with the most horrifying part of the movie, the creature’s life cycle – one in which a “face-hugging” larva implanted eggs into its host (poor old John Hurt) resulting in the infamous chest buster scene – made it the most dreaded space monster in cinematic history.

The success of Alien brought a wave of 1980s alien invasion movies that are considered by many critics and fans alike, to be some of the best offerings the subgenre has ever produced. John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of The Thing from Another World (itself an adaptation of John W. Campbell’s important novella) The Thing was not well-received upon its release, just a few weeks after Spielberg’s heartwarming E.T. But The Thing‘s apocalyptic tone and revolutionary practical effects have made it a classic in both the horror and sci-fi genres, and widely considered to be at the top of the list of Carpenter’s impressive body of work. Phantasm, low budget feature about a creepy alien called The Tall Man (Angus Scrimm) who came to Earth to turn our dead into dwarf slaves for his home world has become a horror classic. Other films drew big box office numbers like Predator and They Live. NBC even aired a popular mini-series in 1982 called V about a race of seemingly human-like visitors who arrive with a message of galactic friendship but have secret plans to take over the Earth. Horror author Whitley Streiber published a non-fiction account of his claimed alien abduction in 1987, called Communion that was adapted to a film the next year starring Christopher Walken. The film was not a big hit, but it helped to popularize “the Grays” as a form of alien iconography that would become ubiquitous in the coming years.

Horror in the 1980s was nothing, if not fun, and a fair number of alien invasion movies added some comedy to the mix. Killer Klowns from Outer Space, a movie that sounds exactly like what it is was made by effects artists, the Chiodo Brothers and features a wide array of killer alien weapons disguised as popular circus gags. The 1986 creature feature, Critters came off the success of a Gremlins-inspired wave of movies about little monsters, and had some pretty adorable little monsters with very large teeth. Larry Cohen’s The Stuff was about an invasion by a strange extraterrestrial fluffy material that looks and tastes delicious, but turns consumers into mindless slaves. Similarly, Night of the Creeps was essentially a zombie movie about intergalactic slugs who take over human brains.

After the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the United States took its place as the world’s sole-superpower, American culture began to answer the question of what would happen when there is no mortal enemy out there to fear. It turns out, we seem to need some form of angst in order to function, so a lot of people looked for smaller crises anywhere they could be found. Aliens helped. In 1993 Fox launched the hit TV series The X-Files about a pair of investigators who focused on cases related to the paranormal, especially those pertaining to extraterrestrial visitation. The show seethed with a vibe of alien conspiracy thinking that made it huge television phenomenon. The X-Files aired during a time when the UFO panic of the post-war years was making its way back into mainstream culture. But in the final decade of the twentieth century, it wasn’t just a series of disconnected “truthers” making claims about extraterrestrial encounters, but a network of believers was increasingly able to form a larger community with the emergence of the Internet. In 1994, Harvard psychiatrist John E. Mack published Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens, a work that took seriously the claims of hundreds of patients he’d treated who claimed to have had such run-ins with extraterrestrial invaders, giving an air of legitimacy to these reports. And alien t-shirts and merchandise with images of gray or green men with large heads and big black eyes seemed to be everywhere.

In the absence of Cold War conflict, alien invasion movies during that decade lacked the thematic cohesion of their predecessors and perhaps benefited from this. The 1993 drama, Fire in the Sky, was a purportedly true story about an Arizona logger who is abducted by a UFO was just the film for the time, and its alien encounter is quite frightening. Species was more of an action film, but its alien antagonist was an escapee from a government lab where DNA sequence from an extraterrestrial signal was spliced into a human embryo, which went just about as well as you might expect. One of my favorite movies of the decade 1998’s Dark City, takes place in some undisclosed city that looks like it came straight out of a 1940s film noir. There, mysterious extraterrestrial beings are manipulating human memory to some strange end. The 1996 big budget Independence Day was a triumphant and jingoistic updating of the older 50s blockbusters, and reflective of the relative international tranquility of the era. But that tranquility was about to be smashed and aliens would come along for the ride.

Officially, the twenty first century began on the first of January, 2000. But thematically, it crashed into history more than eighteen months later with the attacks of September 11, 2001 on the World Trade Center in New York and the The Pentagon. This event was followed by more than two decades of war, terrorist attacks, mass shootings, financial crashes, political polarization, and a global rising tide of authoritarian and reactionary politics that has everyone on edge. And that was before the 2020 pandemic that killed nearly seven million people globally and the recent spate of anxiety around the rapid development of artificial intelligence. Predictably, horror fiction has boomed in the light of the widespread unease that has so far marked the first quarter of the new century.

For my money, the last two decades have provided us some of the finest alien invasion films ever produced. The year after the 9/11 attacks, M. Night Shyamalan released Signs about a global alien invasion but its feel good story seemed to be a throwback to a more tranquil time. It did respectable box office numbers, but it did not set the tone of films to follow. Aliens were about to become dark reminders of the dangerous world we live in. One of the first movies to explicitly embody the horror of 9/11 was Cloverfield, J.J. Abrams big budget 2008 found footage feature about a group of party goers trying to escape the New York City as it is ransacked by giant aliens. For its dark associations with horrible events, the film would prove to be on the tamer end of nihilism spectrum the century has produced. District 9 (2009) gives an unpleasant look at what might happen if aliens did land but in contrast to the standard invasion formula, the extraterrestrials learn very quickly about the cruelty their new hosts are capable of inflicting on outsiders. Monsters, a 2010 independent film about giant extraterrestrials in Mexico launched the career of Gareth Edwards. Honeymoon takes place in a secluded cabin where a pair of newlyweds sees strange lights in the sky that signal something bad is about to happen. They Look Like People is a modern take on paranoia, in the vein of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but with a tone for the millennium. Coherence has an alien invasion that warps time and space, ruining a dinner party in the process. Under the Skin (2013) looks at an extraterrestrial hunter who lacks any human emotion and gave perhaps the best exploration of what might motivate a non-human intelligence. In Annihilation, Alex Garland’s 2018 story about an alien infected zone in Florida, we are given no sense of what motivates the invader and are left with the sort of cosmic horror the likes of which H.P. Lovecraft envisioned a century earlier. But not every cinematic space invader is a metaphor for twenty-first century anxieties. Some like Slither, made by James Gunn before his entry into the Guardians of the Galaxy series, is just straight up alien fun. Attack the Block a British urban comedy, and Edgar Wright’s The World’s End are not without social commentary, but neither sacrifices laughs or thrills in the process.

Those old paperbacks from the 1950s with covers featuring flying disks and green-tentacled monsters have mostly disappeared from the shelves. There have been a number of new literary takes on the concept of alien invasion that have explored the topic in ways that would surely make H.G. Wells proud of what he started more than a century ago. The film, Annihilation was an adaptation of the first entry in Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, a nearly impenetrable story about a strange phenomenon that infects Florida. The Spin trilogy by Robert Charles Wilson begins when the stars go out one night and the inhabitants of Earth learn that the planet has been surrounded by a massive shield that causes time to slow down. I’m currently two-thirds of the way through Chinese sci-fi author’s Liu Cixin’s Remembrance of the Earth’s Past series that begins with the bestselling Three Body Problem in 2014 and proceeds to tell the story of humanity’s response to an alien invasion in progress that will take place four centuries after the story begins. It is a masterclass in hard science fiction and humanity’s mixed response to the extraterrestrial threat that rings true after our recent collective experience with COVID 19.

I doubt many people would contest the fact that the last decade or so has been a strange time. A reality television star’s circus of a campaign and presidency, the bonkers media environment that surrounded it, and a global pandemic have all contributed to a world has become a place where our threshold for the unusual has been drastically lowered. Throw in some widely-circulating conspiracy theories about mind-controlling chem trails, lizard people, and a flat earth and we are practically living in a dark comedy. Why wouldn’t there be flying saucers front and center in the news cycle?

Without a doubt we have seen an increase of UFOs in recent years, or as scientists now call these unidentified flying objects, UFPs – Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena. The current wave of interest began in 2017 when an unusually-shaped object moving in odd patterns was sited flying through our solar system. The elongated cigar-shaped body measuring somewhere between 100 and 1000 meters in length was named Oumuamua (Hawaiian for “a messenger from afar arriving first”). While most scientists studying the object hypothesized that it was a comet or asteroid, maybe even the shard of a broken planet, others suggested there had to be intelligence behind it. Harvard astronomer, Avi Loeb even wrote a book with a compelling argument that the anomalies present in the celestial body can only be explained by looking at it as a genuine piece of alien technology. Most of the community has since concluded that Oumuamua is an interstellar comet, but it was only the beginning of strange anomalies in the sky.

Just two months after Oumuamua was spotted, a number of videos surfaced showing inexplicable activity in the heavens closer to home. The New York Times published a story featuring two leaked videos taken by US Navy pilots who shared the sky with some very unusual objects. The first of these taken in 2004 by Cmdr. David Fravor off the coast of San Diego shows what appears to be a white “tic tac-shaped” craft moving in a trajectory that is not physically possible by any known terrestrial aircraft. The UFP seemed to mock Fravor’s own flight pattern before disappearing into thin air. A number of other videos began to appear all of which were speculated to be the same object. A spokesperson for the Pentagon confirmed the authenticity of the video and former president Barrack Obama even chimed in on the topic, “there’s footage and records of objects in the skies that — we don’t know exactly what they are, we can’t explain how they moved, their trajectory.” Of course, none of this means we have video footage of alien spacecraft but it does confirm that something weird has been happening that no one, even those in the highest echelons of power can quite explain.