For two thousand years, Christians have been debating many of their faith’s most basic doctrines, sometimes waging destructive wars over what to outsiders might seem like tiny points of difference. There is an oft heard claim that there are thirty-three thousand Christian denominations, each one claiming to have the correct understanding of religious truth. This number is a bit of an exaggeration, but it does highlight the fact that there is a very wide set of sometimes mutually exclusive beliefs around what it means to be a Christian. There are a few basics that almost all agree on, though. Very few believers doubt the foundational story that, in order to redeem humanity from its sinful nature, God the Father sent his only son to Earth in human form. Jesus, The Son, preached for three years, performed astounding miracles, and revealed himself to be God incarnate. He was betrayed by his disciple, Judas, for thirty pieces of silver, captured by the Roman authorities at the behest of Jewish religious leaders, tortured and crucified on a Friday and died. Three days later he rose from the dead and in so doing, opened the doorway for humanity’s redemption with his blood sacrifice. While they might disagree about when Jesus was born or whether that date is worthy of celebration, nearly every Christian recognizes that the Easter story – the commemoration of Christ’s resurrection – is the central drama of their faith.

As I’ve said before when writing about the histories of Halloween and Christmas, no holiday was ever born in a cultural vacuum and traveled through time and space without being changed in fundamental ways from its initial inception. Christians may all agree about the truth of Easter’s central narrative, but there is an infinite number of ways to commemorate that truth. Religion Studies scholar and amateur holiday specialist Bruce David Forbes argues that, broadly speaking, our popular holidays rest upon three foundations. That is, the major holidays we mark on our calendars sit on top of different layers of human experience that have shaped the way we think about them.

First, there is a seasonal element bound up with climactic conditions and agricultural patterns that set the tone for the rhythms of people’s everyday lives. Planting and harvest, seasons beginning and ending had major effects on farming communities, and they became times worth noting and celebrating. These universal experiences were filtered through a second foundation, the local religious or national belief systems that gave people ways to interpret the meaning of those seasonal patterns and added further particularity to the holiday. Whether religious or secular, we all view these ancient celebration through the filter of the third component, modern culture. Increasingly secular, cosmopolitan and driven by commercial and consumer impulses more than agricultural ones, they have gained new meanings over time, sometimes in conflict with earlier ones. The tilt of the Earth and its solar orbit gave us the winter solstice. The church gave us the Nativity. And capitalism gave us Santa and Black Friday. They all swim together in the cocktail we call Christmas.

Forbes’ model works very well for Easter, too.

The vernal equinox is one seasonal pattern that tickles the celebration response in people everywhere, especially if they live in climates that experience cold winters. Iranians still observe the first day of Spring as the beginning of the new year with a three-thousand year old festival called Nowruz (“New Day”). The day kicks off two weeks of festivities including lots of universal spring symbols; green plants, colorful flowers, and candles and bonfires that symbolize the return of light and warmth. The Chinese New Year is a multi-week jubilee culminating in the Spring Lantern Festival, a celebration going back to the Han Dynasty when Emperor ordered everyone in the kingdom to light lanterns to honor the coming season. May Day has become synonymous with the modern labor movement, but it originated as a Spring festival in ancient Egypt. Celebrants gathered flowers and wore bright colors while dancing around large fires to honor the sun’s gift of light and warmth. Spring all over the world is represented as a time of birth, creation, and renewal.

Easter does of course share many thematic aspects with these other celebrations by virtue of the fact that people tend to have universally similar responses to seasonal changes. One spring festival in particular though, is a direct antecedent to the Christian holiday. The Jewish festival of Passover commemorates the Israelites’ flight from bondage in Egypt after being enslaved for centuries. The name of the holiday comes from a rather grim passage in Exodus in which Yahweh executed all of the first born Egyptian sons as a punishment to Pharaoh and his people. In order to distinguish Jewish and Egyptian sons, God ordered each Israelite family to slaughter a lamb and paint its door with the animal’s blood so that the Angel of Death would know to “pass over” their home. But per Forbes’ model of layering new traditions over existing ones, the practice of sacrificing a lamb at the beginning of spring is much older and very widespread in near eastern cultures and undoubtedly Jews took part in such rites long before the flight from Egypt. Passover then, was a way of particularizing what a widespread custom to a local experience.

With Easter, Christians added another layer on top of this growing holiday tower. The Last Supper that took place just days before the crucifixion and resurrection was a Passover meal, at least according to the synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. John, however, saw it fit to set the crucifixion itself on the day of Passover. Most Biblical scholars assume that this editorial decision was taken in order to align the death of the sacrificial lamb, with that of Jesus who shed his blood that sins could be forgiven. In either case, the Easter story was told within a pre-existing religious context and this was no accident. Just as the chroniclers of the Israelite flight from Egypt set their narrative within the older tradition of spring sacrifices, so too did the founders of the new religion choose to insert their accounts of Christ’s death and resurrection into the dominant social narrative in order to impart legitimacy to the gospel tales.

Easter is not mentioned in the Bible and in fact, early Christians continued to celebrate Passover for hundreds of years after the Crucifixion of Christ. The question of whether or not Christians were a Jewish sect or a new religion was debated for centuries and the controversy over whether to observe Passover or Easter was a central theme in this debate. The ancient kinship between the two holidays is preserved in modern language. The Greek word for Easter, Pascha, was adopted from the Hebrew Pesach, meaning Passover. This is true of most European languages today (French, “Pâques”, Spanish and Italian, “Pascua”, Dutch “Pasen”etc.). A Christian and a Jew today will undoubtedly have very different senses of purpose when celebrating their respective holidays, but each is beholden to traditions larger than their own memories, traditions built upon layers of symbolic meaning that has traveled through a lineage originally born of the vernal equinox.

It is fair then to say that Easter evolved from Passover just as Christianity in many ways evolved out of Judaism. Nonetheless, there are symbols that have become associated with the holiday that seem to have nothing to do with either tradition. It is easy to assume then (and some have claimed) that whatever its religious roots, modern day Easter has taken on a great deal of “pagan” window dressing. I have discussed elsewhere how Halloween and Christmas were rooted in pre-Christian holidays, and the practice of “appropriation not confrontation” of “pagan” rituals and festivities was explicitly made a church policy with a letter by Pope Gregory I to a mission to England in the seventh century. The church has engaged in borrowing and absorbing traditions, but is Easter an example of this?

Bede, the eight century monk who wrote the earliest history of the England, linked the English word “Easter” with the Anglo-Saxon fertility goddess Eostre, though outside of Bede’s writings there is no evidence that such a god was ever even worshiped. In the internet age, one can also find claims linking the holiday with the Mesopotamian fertility goddess Ishtar who is often associated with springtime. We can dismiss the latter out of hand as there is no evidence to support it, but Bede’s claim has a bit more weight. Why after all, would a Christian apologist invent a story that contradicted his mission? Bede claimed that Eostre’s older festival day accounts for the German word for Easter, “Ostern” (from which the English name is derived) and it’s easy to extrapolate from there that Christian missionaries tried to sneak Pascha into the existing cultural tradition. There are no records outside of Bede’s short account on this topic to suggest this is true, but nonetheless it is conceivable. Even if this is so, the process was much different from the ones in which church leaders co-opted Samhain and the birthday of Sol Invictus into Halloween and Christmas by maintaining the structure of the “pagan” celebrations while giving them a Christian veneer. If the Germans and Anglo-Saxons used the name of the fertility goddess to celebrate the resurrection, they left the Christian rites fully intact.

All well and good, but what about The Easter Bunny and the magic eggs he delivers on Easter morning? Surely, these are “pagan” accretions? What could they possibly have to do with the death and resurrection of Christ? It is true that by the time Christianity came along, eggs and rabbits had a long established history within the annals of myth and folklore. Whether, Christians stole or co-opted these, is a bit more complicated.

Like springtime the egg has long symbolized birth and creation. In many cultures across the old world, the universe or the gods that made the universe were hatched from a cosmic egg. The Egyptian sun god Ra was born of one that had been molded by Khnum the sculptor of the universe, as did the primordial deity, Phanes, according to an ancient Greek religious tradition called Orphism. The sacred Upanishads of India viewed the universe as a massive egg with the shell representing the outer edge of reality, the albumen the sky, and the yolk as the Earth. In some Taoist creation stories, the cosmic egg was broken by a god named Pan gu who split two sides of the shell into heaven and Earth. In Zoroastrian cosmology of ancient Persia, the Earth was encased in the sky which formed an egg-shaped protective layer around it. All was happy in the cosmos until Ahriman, the lord of all evil cracked the outer shell, penetrated the world, and brought corruption with him. In the Australian aboriginal Dreamtime tale of Dinewan the emu and Brolga the dancing bird, the sun was formed when the two sacred creatures got into a big argument in the time of eternal night. During the conflict, Brolga hurled one of Dinewan’s eggs into to the sky. and it landed in a nearby campfire that caused the sizzling to yolk to rise and light up the sky.

For thousands of years, sorcerers and witches have practiced oomancy an art whereby eggs were cracked into boiling water in order to divine the future within the shapes the whites formed. In English lore, girls would often eat boiled eggs on a stormy night so that they might dream of the man they would one day marry. Eggs have also been seen as a means of ensuring fertility. English women once rubbed their bellies with unbroken eggs hoping for magical aid in getting pregnant. Similarly German farmers have long opened the spring planting season by smearing yolks on their plows to inspire a productive harvest. Others buried eggs in the ground to encourage crops to grow. Eggs could protect the home as well which is why farmers often threw small ones over their roofs in hopes that they would distract the attention of any nearby witches.

The most famous eggs from folklore is actually something of an impostor. “Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall…” I don’t need to finish the nursery rhyme; you’re doing it in your head right now. It’s almost certain that you’re also picturing an anthromorphisized egg as you do so. Go ahead and recite the poem again, this time try to pinpoint where it is suggested that Humpty is an egg. The origin of the nursery rhyme is unknown, but scholars believe it goes back to the English Civil War of the mid seventeenth century and refers to a giant cannon (“Humpty Dumpty” is old English slang for a large person). In a bit of bad luck, the king’s big gun fell off of its rampart where Royalist forces were holding up and all of the king’s cavalry (horses) and his infantry (his men) couldn’t repair the doomed weapon. The egg-shaped Humpty we all know was born a couple of centuries later, given to the world by Lewis Carroll in his 1827 novel, Through the Looking Glass. Alice comes upon the large egg with arms, legs, and a face, sitting on a wall and recognizes him immediately, as the character from the old nursery rhyme. I can’t say what inspired Carroll to depict Humpty in this way, but then again, I couldn’t begin to explain half of the author’s wild imagery.

During traditional Passover Seder meals, an egg is placed on the table though there is some debate as to the meaning of this tradition. It may actually have been influenced by a similar Nowruz tradition of placing an egg on the haft sin table to symbolize fertility. It is also possible that the Persian tradition directly influenced Armenian Christians who in turn inspired the legendary decorated eggs of their eastern co-religionists (more on that below). The Ukraine, known today for its amazing decorative Pysanka (“Easter”) eggs dedicated to Christ once did so for the sun god Dazhboh. Given that coloring eggs in the spring is seemingly a widespread tradition throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa, it is very difficult to pinpoint a single source of inspiration.

Early Christians may well have been influenced by the symbolism of the egg in any of these traditions, but the doctrines of the church readily found meaning in the egg without needing to co-opt it from elsewhere. To the church fathers, the hard outer shell represented the walls of the tomb, walls that cracked like an egg when Christ rose from the dead. Eastern Christians have long colored eggs red to symbolize the blood of Christ since the earliest days of the church. In Russia and Ukraine there is a tradition of ornate egg decorating that puts my childhood Paas designs to shame. According to a popular tale, Mary the mother of Jesus laid down a basket of eggs next to the cross when she visited her dying son and his blood dripped into the basket staining them red. Simon of Cyrene was said to be carrying a basket of eggs when he was forced to help Jesus carry his cross to the hill upon which he was to die. When he returned, his eggs had changed into an array of colors. Another tradition held that Mary of Magdalene brought eggs when she visited the tomb of Christ that instantaneously changed to all the colors of the rainbow when she found the entrance had been broken open.

Christians of noble birth have exchanged gifts of elaborately colored since at least 1291 when English monarch, Edward I ordered hundreds of eggs to be painted and given to his family on Easter morning. The tradition spread throughout western Europe and within a century, manorial lords could expect from residents across their domains. None matched the intricate design work undertaken by Eastern Christians, particularly those of Peter Carl Fabergé, whose gold and jewel-encrusted eggs were exchanged as gifts by the Russian royal family from 1885 to the Russian Revolution when the Bolsheviks sold them off to collectors to pay for their faltering government.

Christians traditionally abstained from eating eggs during Lent and as a result ended up with a surplus of eggs leading up to the holiday. If they can’t be eaten, they might as well get decorated. Better yet, they could be used to play games. In Lancashaire, England there is an Easter custom going back to the Middle Ages known as Pace Egging (Pace being an old English derivation of “Passover”). Originally, eggs were boiled with onion skins to give them color. On Easter morning, children paraded in costume (a practice that was once a generalized holiday tradition) and were given the decorated eggs as treats. These days, eggs are usually painted during the festivities and children participate in a contest to see whose Easter eggs can roll the furthest down a hill without cracking. This tradition is kept alive on both sides of the Atlantic. Since 1878, the White House has hosted an annual event in which children roll eggs across the South Lawn.

Martin Luther, the sixteenth century Protestant reformer was no fan of “pagan” traditions adopted by the church and he spent his life trying to do away with any practice or belief that was not firmly grounded in Biblical authority. Yet, he found no problem with the use of decorative Easter eggs. In German lands where Lutheranism was adopted, it became a popular activity for men to hide colored eggs for women and children to find on Easter morning, a celebration of the women who found Christ’s empty tomb. Within this same tradition, Easter’s most recognizable modern icon was born.

On the surface, The Easter Bunny also seems to be intuitively a pagan symbol. What does a talking rabbit who travels around the world delivering candy have to do with the Resurrection of Christ, after all? If you Google “Easter Bunny” you will find lots of articles suggesting that the rabbit was a companion animal of the goddess Eostre who you’ll recall from above, may or may not have existed. The idea was first suggested by folklorist Jakob Grimm in his 1835 work, Deutsche Mythologie. No doubt inspired by Bede’s claim on the German name for the holiday, Grimm suggested that the Easter Hare was descended from the fertility goddess’ companion animal, but there doesn’t seem to be any convincing evidence that such a tale exists outside of Grimm’s imagination.

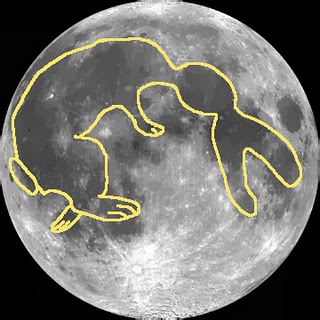

Nonetheless, the rabbit (and its close relative, the hare) does appear in non-Christian mythological traditions across the world. In East Asian lore, rabbits are one of the twelve signs of the Chinese Zodiac. In fact, my year of birth was the year of the rabbit and, though I like to think of myself as creative and polite as those born under that sign are said to be, I somehow missed out on the networking and business acumen I’m supposed to possess. According to Japanese legend, the “man” we see in the moon is actually a rabbit. I just looked for a rabbit for the first time during last month’s full moon, and now I can no longer see the large gray basalt plains, Mares Nectaris and Fecunditatis as anything but large bunny ears. In many Japanese children’s stories, the moon is populated with rabbits who make concoctions ranging from elixirs of mortality to the delicious dessert treat, mochi. The rabbit stars in one of my favorite Jataka tales – stories about the Buddha’s previous animal lives. A very kind hare comes across a starving holy man and, feeling pity for the man’s plight, he throws himself into a fire to be cooked so that the hungry sage might eat. The fire immediately disappears and the man reveals himself to be a disguised deity who came to test the hare’s commitment to generosity. To reward the hare’s selflessness, the god imprints the animal’s likeness on the face of the moon.

In African folklore, the rabbit is often considered a clever trickster who easily escapes difficult situations (we see traces of this theme in the antics of modern day characters like Peter Rabbit and Bugs Bunny). This tradition is was brought to North America by slaves and preserved in the story of Brer Rabbit an old African American folk tale about a clever bunny who manages to constantly outsmart the larger animals that are trying to eat him. In a Japanese myth, the Hare of Inaba is desperately trying to cross a wide bay, but is unable to find a way, so he tricks all of the nearby sharks to form a straight line from shore to shore. He jumps from back to back to cross the water and nearly makes it unscathed, until the final shark in the line, none to appreciative of the hare’s ruse, bites the little trickster and pulls off his skin just as he arrives on the other side. Aztecs who’d had a few too many glasses of pulque (a strong fermented alcoholic drink) had a saying that they were as drunk as four hundred rabbits. Mesoamerica tradition held that there were four hundred (a number associated with infinity) ways to become intoxicated and there were a whole pantheon of drunken rabbits manifesting these various levels of drunkenness. In Aesop’s fable, “The Hare and the Tortoise“, the speedy mammal is perhaps a little too clever for his own good when he is beaten in a foot race by his much slower opponent.

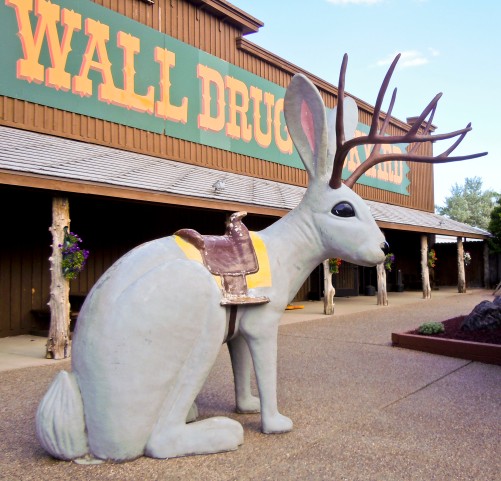

Even at their most mischievous, rabbits and hares are generally portrayed as gentle, but in some legends, they can be monsters. The jackalope, a jack rabbit/antelope hybrid, has been a source of strange rumors and a popular feature of modern American folklore since hunter and amateur taxidermists Herrick Brothers from Wyoming stitched a pair of antlers onto a jackrabbit in the 1930s. They sold the mounted head to a local hotel, and the creature quickly became famous and a wide array of stories circulated as a result. The Belgian myth of the Oschaert is of a spirit that haunts the town of Dendermonde in Belgium. It usually appeared as a black dog that attacked sinners but at times he might appear as other animals, including a rabbit. In Filipino mythology there is a creature known as the sigbin that is often compared to the Puerto Rican legend of the chupacabra. The vampiric creature is said to have legs like a jack rabbit and the head of a goat and spells doom for children caught wandering outside at night during Easter time.

The most enduring trait associated with rabbits in folklore is that of luck. I used to get really squeamish about the multi-colored lucky rabbit’s feet that everyone seemed to carry around on their key chains in my youth. Apparently, this was not some mere 1980s trend – a more sadistic version of Trolls or Rubik’s Cube – but a long standing tradition going back millennia. The luck of the severed foot is made exponentially more effective if the rabbit is killed in a graveyard, especially if done on a full moon that falls on Friday the thirteenth, even better if the person doing the killing is cross-eyed. It’s probably a lot easier to just say the word “rabbit” at the beginning of a month to ensure that the days ahead will be fortunate ones, as was often done by superstitious folks in England. Young children were often given white rabbits, a gift that would help them towards more prosperous lives. The origin of the association between the rabbit and good fortune is likely linked to their ability to reproduce very quickly, a result of lots and lots of sexual activity. No doubt, Hugh Heffner was thinking along the same lines when he chose the bunny to be a symbol of his hedonistic empire.

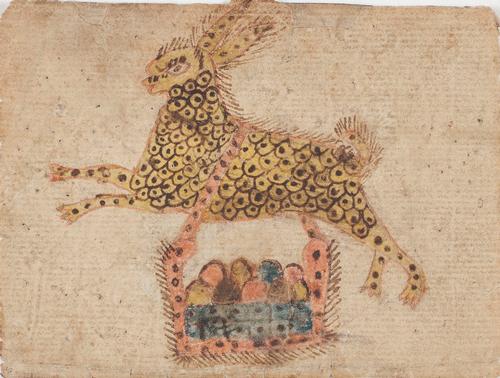

The traits exhibited by rabbits (real or imagined) fit well with Christian doctrine. From antiquity until medieval times, it was commonly believed that rabbits could reproduce without mating and thus were subject to parthenogenesis (that is, virgin birth) giving the animal its long association with the Virgin Mary. Given the frequency of rabbit copulation, it’s hard to imagine how everyone missed catching a glimpse of bunnies in action, but, alas, conventional wisdom dies hard. The ancient three-hares motif that appears across Eurasia, in which three interlocking rabbits (or hares) also found a home in Christian churches as a symbol for the Holy Trinity. Rabbits appear across medieval Christian imagery, sometimes as a sign of peace and gentleness, others as a stand-in for the Virgin Mary. Some medieval monks turned this imagery on its head with a very odd tradition of drawing pictures of homicidal rabbits in the margins of illuminated manuscripts engaging in various acts of violence against humans. There is no historical documentation as to what the reason behind these graphic but humorous images. It may be that they were exactly what they appeared to be; absurd images meant to amuse the artists.

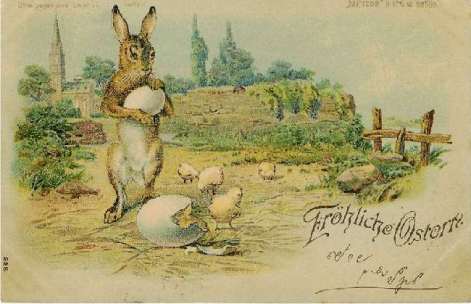

The Easter Bunny originated in sixteenth century Protestant Germany around the same time that Martin Luther was holding his egg hunts. According to legend, a German mother hid colorful eggs in the garden for her children to find. In the morning the kids spotted a hare hopping away and assumed that the hare must have come secretly in the night to deliver the colorful gifts. Stories began to spread across the land about the Osterhase (Easter Hare) and German children began to set up nests the night before Easter and wait for the Hare to arrive. In 1682, Georg Franck von Franckenau made the Hare famous with an essay about how he laid magic eggs for children across Christendom. Parents gladly adopted the symbol as a form of behavior management for children, with good ones receiving the reward of colorful decorated eggs on Easter morning. The Osterhase came to the United States along with the Pennsylvania Dutch community (who were German, not Dutch) in the seventeenth century and as with other imported holiday traditions, enterprising American retailers saw in it an opportunity to make some major money. On the heels of the taming of Christmas in the mid-nineteenth century, Easter became a prime time for the newly dubbed Easter Bunny to deliver mounds of candy to kids across the United States.

The Easter Hare became the Easter Rabbit who is now, well, you know who he is. Along with commercial egg decorating kits made by producers like Paas (notice the linguistic connection with Passover) The Easter Bunny became a marketing tool in the late nineteenth century, appearing on greeting cards across Europe in the U.S. Rankin-Bass, the great purveyor of the modern Christmas mythos took a few cracks at Easter as well, and in the process turned the bunny into a holiday icon. The 1971 special, Here Comes Peter Cottontail featured the song of the same name, originally performed by Gene Autrey, the singing cowboy who had popularized such Christmas hits as “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and “Frosty the Snowman“. Rankin-Bass later went on to give the Easter Bunny a modern origin story (just as they did with Santa a few years earlier) in the 1976 movie, The First Easter Rabbit. The feature film Hop, is a favorite of my kids about the heir to the office of the top Bunny himself who would much rather play drums in a rock band than deliver decorated eggs. The 2012 animated film Rise of the Guardians featured the voice of Hugh Jackman as E. Aster Bunnymund who has to team up with Santa, The Tooth Fairy, and several other folkloric figures of childhood to stop darkness from engulfing the world.

Unlike other holidays, Easter is the one indispensable celebration of the Christian faith, and as such it is probably the one most firmly based in both scriptural writings and lived tradition. Nonetheless, holidays don’t last as long as Easter has without collecting new customs and shedding old ones as they travel through time and are taken up by new people. Nor can firm borders be drawn around them to keep out symbols that may resonate with later generations. I suppose that is why a non-Christian like me who are not committed to the truth of the Resurrection can nonetheless enjoy watching our kids run through our yard on a beautiful spring morning searching for colored, candy-filled eggs just as committed Christians have done for centuries.

Next month I will be following the historical and mythical journey of one of my favorite foods, the chili pepper.

5 thoughts on “Another Synaptic Holiday History Part 1: From the Resurrection to the Rabbit”