When I was about five years old my mother bought me a set of markers which I immediately proceeded to use to color all the places I could reach on my body the color brown to make myself into a werewolf. I think my motive was mainly to scare my upstairs neighbor, but even more than that I just wanted to become my favorite monster. I don’t remember why this was so, but even at that young age, I picked up on the fact that the wolf man was a much more interesting antagonist than the vampire or zombie or any of the horror icons I loved. While those others were figures of pure evil, the werewolf was a part time fiend, a reluctant killer who was very dangerous, yes, but who, during most of his existence, just wanted be a regular person. Maybe I was able to sense this at a young age because this archetype speaks to something deeply instinctive; it is a rather on-the-nose (or shall I say, on the snout?) metaphor for the human condition. Each of us has a beast inside that we (hopefully) learn to control as we get older. But for the werewolf, that inner-monster is untamable, and regardless of the intentions of the unfortunate person who bears the curse, people almost always get hurt.

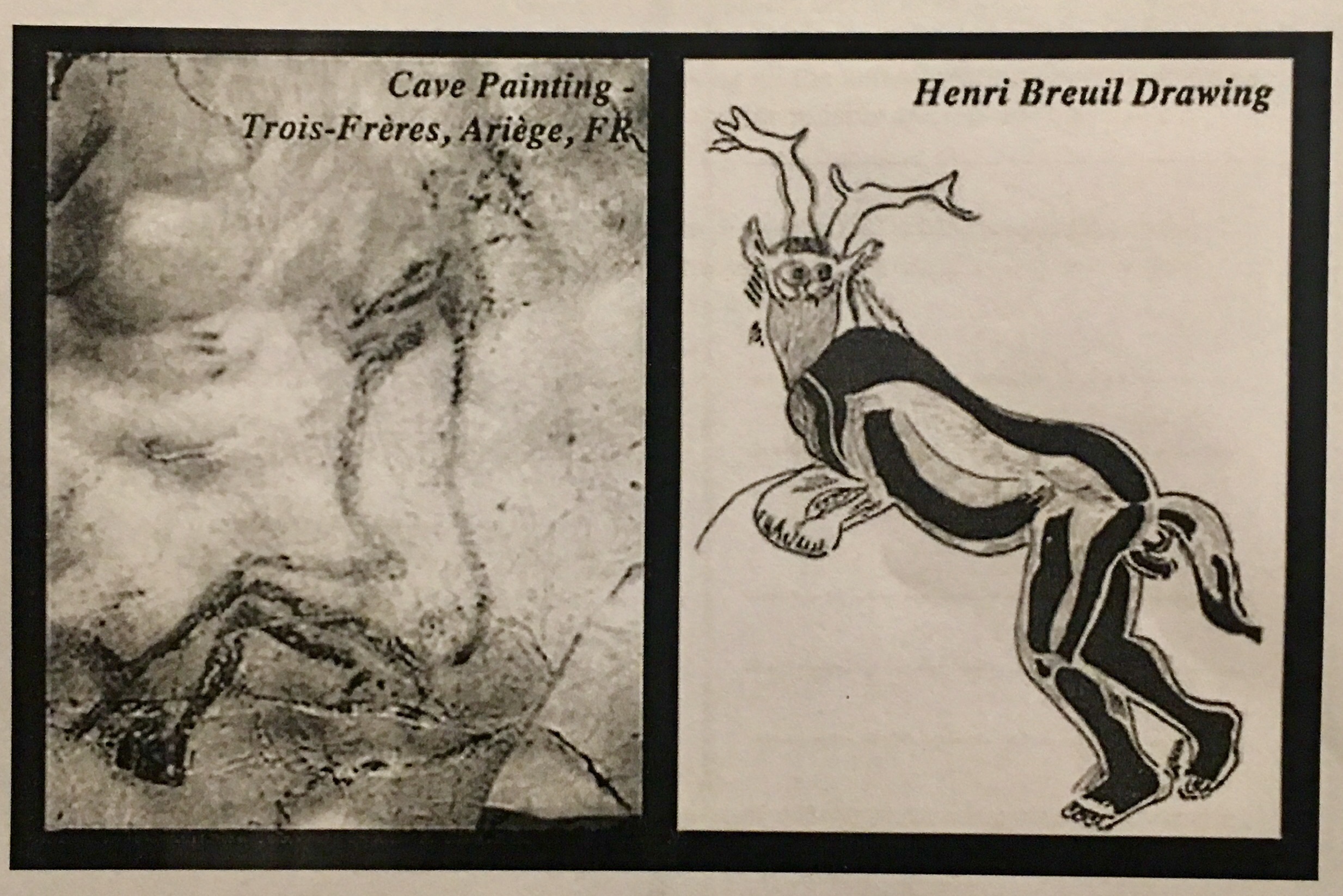

Transformation from human to beast is a recurring theme found in just about every myth tradition on Earth. One of the oldest known pieces of human art, a cave drawing dating back to approximately 13,000 BCE features a figure that combines the features of a human and a stag. The picture was discovered in “The Sanctuary” a cavern in the Trois-Frères cave in Montesquieu-Avantès, Ariège, France on the eve of the first world war, but was popularized in the 1920s by anthropologist Henri Breuil who sketched an image of what he thought the drawing would have looked like when it was freshly painted. Breuil called the figure “The Sorcerer” and hypothesized (controversially) that it depicted a shaman who had taken animal form. Human/animal hybrids have been discovered in other paleolithic sites and theme of metamorphosis appears in shamanistic rituals across the globe. It persisted as we slowly became an agricultural species. The idea that we are only so far away from our animal nature is one that is apparently universal. Folklorists have coined the term therianthropy from the Greek words theríon (wild animal) and anthrōpos (human being) to describe this widespread phenomenon.

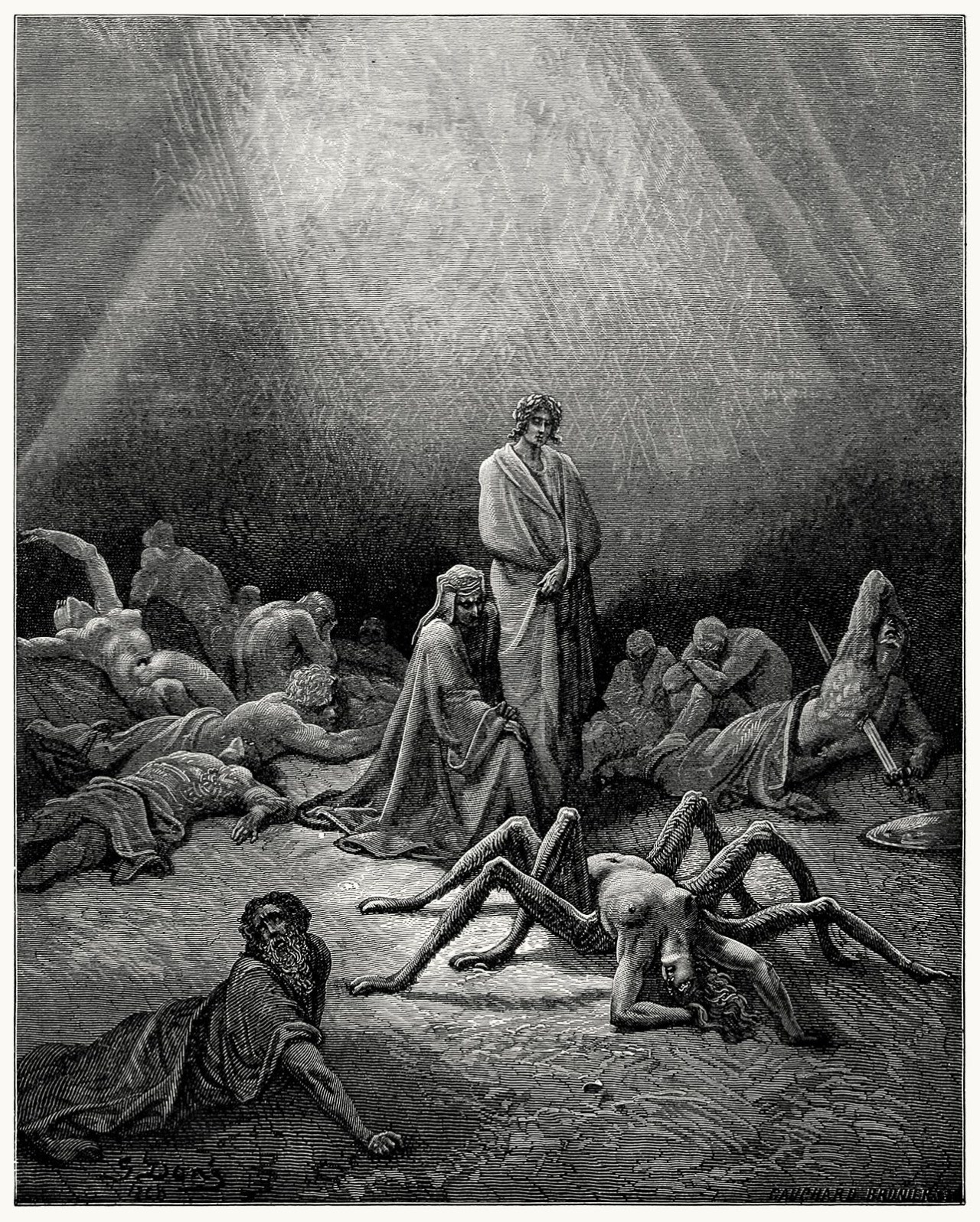

It is fitting that a Greek word was chosen to name this condition given the prevalence of transformation myths in Greece’s ancient past. Arachne was the greatest mortal weaver the world had ever seen, so much so that she came to believe her skills on the loom surpassed that of the gods. Athena, the war goddess did not take too kindly to this sort of hubris so she challenged her to a weaving contest. Arachne turned out to be correct about her talent, and the tapestry she spun was far superior to Athena’s, but as they say, a goddess is never wrong. Angered by her defeat, she transformed the mortal into a spider and Arachne was forced to spend eternity weaving webs. In one of the more tragic tales from ancient myth, Princess Calisto daughter of King Lycaon of Arcadia (more about her dad and homeland below) ran into some problems after being impregnated by mythology’s most infamous womanizer, Zeus. Depending on the version of the story, her punishment came from Zeus’s ever vengeful wife Hera or from her hunting partner Artemis who had sworn her to celibacy, either way she was turned into a bear for her sexual discretions and then hunted down by her own son.

In sub-Saharan Africa, there is an ancient belief that noble kings could return from the dead in the form of large cats. In the Tsavo region of what is today Kenya during the late nineteenth century a pair of unusually large man-eating lions dragged off dozens of railroad workers from British camps. Local legend claimed that the lions were ancestors defending their lands against the unwelcome invaders. Indonesian villagers who lived close to the world’s largest cats, lived in fear of being stalked by a demonically-possessed person called a Harimau jadian, who through black magic was cursed to become a tiger at night. Throughout South and East Asia, other people believed certain rural tribes were tigers disguised as humans. In Thailand, the idea is reversed and a tiger who eats enough human flesh may turn into an evil human therianthrope.

Similarly themed legends pervaded even across the Atlantic. One of the most visible examples can be seen in the artifacts left by an ancient people that archaeologists call the Olmecs who built an advanced urban civilization in southern Mexico between 600 BCE and 350 BCE. The Olmecs built a number of giant statues depicting a figure that has come to be known as “The Were-Jaguar”. These large monuments depict human heads with cat-like features though we know very little about what these mysterious animal human hybrids were meant to represent. Perhaps they are related to the legend of the nagual found throughout Mesoamerica, that tells of shape-shifting humans who could take different animal forms, often determined by the day of their birth. While these beings could be good or evil, they were usually a product of sorcery and thus to be condemned as monstrous.

The Hawaiian legend of the demigod Nanaue is reminiscent of the werewolf legend, but given that wolves are not native to the island, his curse took the form of a different animal. His mother Kalei was renowned for her beauty, so much so that she came to the attention of the shark king Kamohoalii who changed himself into a human so he could marry her. She became pregnant but before the baby was born, the king returned to the sea never to see his wife or son again. He did leave an ominous message, warning her to never to allow young Nanaue to eat animal flesh. But such divine warnings are never heeded, and the boy one day ate a bit of meat. As a result, he began to undergo changes at night and found himself going to the ocean and changing into a shark with an insatiable hunger for human flesh. As people in his village began to disappear into the ocean the boy came under suspicion that forced him to flee. He tried several times to relocate to new places and restart his life, but every time his desire for eating swimmers got the best of him. Eventually, he was hunted down and killed. As with so many werewolf stories, this is not a triumphant tale of good people killing an evil monster, but rather a tragic story of an unlucky person cursed by his very nature.

The native nations of what is today the southwestern United States have a collection of tales of malevolent animal human hybrids that have become popularized in recent years in part due to JK Rowling’s depiction of them in the Harry Potter series. The so-called “skin-walkers” are most well-known from a being in Navajo lore called a naaldlooshii whose name means “by means of it, it goes on all fours“. This human shapeshifter is usually a shaman who has been seduced into using dark magic that grants him unholy powers. The corrupt sorcerer dons an animal skin that has been enchanted and gains the ability to become a coyote, cougar, bear, or other animal. In order to maintain their power, the skin-walker must kill and devour human flesh. These evil-doers are such objects of fear that the Navajo leaders engaged in a “witch purge” in 1878 that resulted in the execution of forty suspected sorcerers. The skin-walker legend, to the chagrin of many Navajos, has become deeply entwined with modern fictional depictions of European werewolves. This is not a welcome development to many native people, in part because it tends to turn their ancient traditions into a silly cartoon, but also it has long believed that giving the skin-walker attention through words or thoughts increases its power.

I hope it is fairly obvious that there is a strong correlation between the most dreaded therianthropes of any given people’s lore and the apex predators that dominate their homelands. Given the heavily forested lands of Europe it should be clear why the wolf has become its most famous therianthrope. Wolves were widely traveled hunters who became intimate with humans primarily because our livestock served as such an enticing food source. As a result, they became thoroughly integrated into the lore of those who shared the land with them, including the creature that is the topic of discussion here.

One of the oldest known werewolf stories, unsurprisingly, comes from ancient Greece. Lycaon was a king of Arcadia who also happened to be the father of Calisto who you might remember from above, was transformed into a bear for her misdeeds. He was known by some for both his cruelty and impiety. As a result, he, like his daughter, managed to piss off the gods and get himself changed into an animal. In his case, it happened when Zeus traveled to Arcadia disguised as a laborer and began to win over the common people’s devotion. Lycaon did not believe that this uninvited guest in his kingdom was the sky god, and became furious that the imposter had divided his subjects’ loyalty. He hatched a plan to avenge himself by inviting Zeus over for dinner to test his divinity. He served the god a meal of exotic meat that just happened to be the flesh of Lycaon’s own son that he’d had killed and roasted. Zeus was appalled by this act of wickedness and changed the king into a wolf, a fitting punishment for his savagery. You may notice that the king’s name bears a resemblance to the word “lycanthrope” that is used synonymously with “werewolf” this was a very appropriate name for the man who is sometimes considered the first in a long line of cursed wolf men.

The stories of Calisto and Lycaon seem to suggest that there is something weird going on in the land of Arcadia. Given that the region was home to some of the oldest tribes inhabiting Greece who were often viewed by others in the region as backwards and barbaric, it is likely, that these stories were born out of anti-Arcadian propaganda. What better way to demonstrate the savagery of one’s enemies than to suggest that they are not quite human? The stereotype stuck around for a long time. Roman naturalist, Pliny the Elder writing in the first century CE tells a story of the Arcadians that suggests lycanthropy was associated with the remote region for nearly a millennium. According to the legend at certain times, one member of an Arcadian family is chosen,

by casting lots among the family is taken to a certain marsh in that region, and hanging his clothes on an oak-tree swims across the water and goes away into a desolate place and is transformed into a wolf and herds with the others of the same kind for nine years; and that if in that period he has refrained from touching a human being, he returns to the same marsh, swims across it and recovers his shape, with nine years’ age added to his former appearance

But the Arcadians weren’t the only werewolves in the Greek imagination. Herodotus writes in Book IV of The Histories that a group of people called The Neuri who migrated to intensely cold borders of the Scythian homelands in the north driven there by a massive snake infestation that plagued the region. According to rumor – and Herodotus was skeptical that the story was anything but rumor, but it was just too juicy to avoid mentioning – “once a year every one of the Neuri becomes a wolf for a few days and changes back again to his former shape.” The Roman geographer, Pomponius Mela writing a half millennia later also made note of this legend in a book he wrote describing the people of the region.

The Neuri are almost certainly the name of a people living in what is today Ukraine or possibly a tribe called the Balts who lived to the north of Greece. Given the rich werewolf lore of Eastern Europe it is likely that the rumors of the lycanthropic Neuri was born of this tradition. In that region, the werewolf myth is closely related to that other famous monster that it has long cohabitated with from nineteenth century Gothic literature to modern day paranormal romances. I speak of course of the vampire. In fact the words commonly usually used for “vampire” in the region (Greek “vrykolakas”, Serbian “vukodlak “, Lithuanian “vilkolakis“, Romanian “vârcolac“, etc.) are also the name for a werewolf. In many of these places, the vampire is able to transform into a wolf. In others, a person who is afflicted with lycanthropy in life is cursed to rise from the grave as a vampire. This connection was popularized in the seminal vampire novel, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, when the titular villain changes into a “a great, gaunt grey wolf” when visiting the home of Lucy Westenra to drain her of blood.

The most infamous Eastern European werewolf is prince Vseslav Bryachislavich, of the former kingdom of Polotsk (in the current country of Belarus) who was known for his brutal battlefield tactics and burning the great city of Novgorod to the ground in the winter of 1066–1067. This no doubt contributed to widespread rumors that he was a sorcerer who sometimes took the form of a wolf to terrify his enemies.

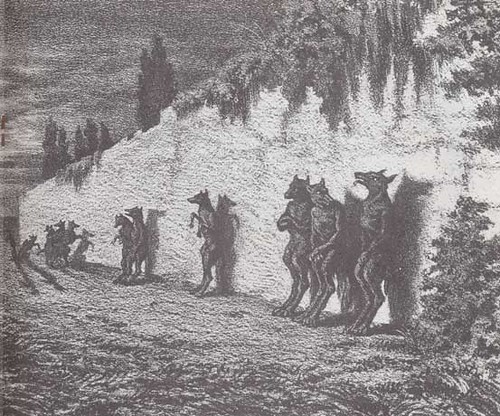

To this day, folklore in Romania and other Eastern European countries holds that werewolves are particularly active around Christmastime. This is probably related to the ancient belief that the solstice was a liminal period during which strange creatures haunted the world. Later werewolves often gained their condition because of blasphemous or sinful behavior and as a result were bound by their master, the devil to taunt the faithful in their holiest seasons. This idea spread west in medieval times. According to Olaf Magnus, a sixteenth century cartographer and historian who wrote in the book History of Goths, Swedes, and Vandals, “at Christmas a boy lame of leg goes round the country summoning the devil’s followers,” who gather together at an abandoned castle as “the human form vanishes and the whole multitude becomes wolves.” These beasts then go marauding in the countryside and:

when a human habitation has been detected by them isolated in the woods, they besiege it with atrocity, striving to break in the doors and in the event of doing so, they devour all the human beings, and every animal which is found within.

To really drive home the malevolence of this accursed creature, Magnusson notes that werewolves are also prone to attack people’s stores of wine and beer and drain them entirely. Savages, no doubt.

Many of the modern werewolf tropes that we know from film and television today were born in the stories told long ago in the heavily forested lands of northwestern Europe. The ancient Celtic champion Laignech Fáelad, was a heroic figure whose name translates to “wolf shapes” often went out with his sons, going:,

wherever they pleased, into the shapes of the wolves, and, after the custom of wolves, kill the herds. Wherefore he was called Laignech Fáelad, for he was the first of them … to go into a wolfshape

He was not the last, though. The medieval Irish history, Coir Anmann records the exploits of a group of vicious mercenaries from the county of Tipperary in Northern Ireland who collectively took the name of their ancestor, Laignach Faelad. According to legend, they could transform themselves into wolf men before going to battle, a skill that made them unconquerable. But they were also dangerous. They worshipped a bloodthirsty god named Crom Cruach and reveled in slaughtering their enemies without mercy. Ireland’s legendary pre-Christian king Tigernmas sought their service to aid him in battle and he figured he had enough gold to pay them, but he miscalculated. The Laignach Faelad demanded payment in the flesh of young infants.

These legends were likely based on exaggerated historical accounts. Roman sources report that in battles against both Celtic and Germanic enemies, they often encountered armies of men wearing animal skins who had taken mind-altering substances that inspired them to fight with great savagery, biting and howling as they charged into battle with no regard for personal safety. Like the Laignach Faelad in Ireland, Germanic warriors frequently wore animal skins. Most famously, the berserkers (whose name means “bear shirt”) robed themselves in fur and made lots of problems for Roman armies who journeyed north. Similarly, the úlfhéðnar (“wolf coats”) were an elite band of soldiers who served first under King Harald I of Norway and fought ferociously. Part of the úlfhéðnar’s cohesion was driven by the fact that were fanatical servants of Odin, who was traditionally accompanied by two loyal wolves, Geri and Freki. Nineteenth century folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould, who wrote the first work on the history of werewolves, directly attributes the emergence of the monster to the legendary exploits of these Celtic and Germanic warriors. who went into battle wearing wolf skins.

But for the Norsemen, the wolf had a dark side that helped shape the werewolf’s monstrous reputation. The Norse word for wolf, vargr is also used for “outlaw” or to describe a villainous person. The end of the world is tied to the Fenrir, a giant wolf who is son of the mischief god, Loki so dangerous that he is chained up in a cell deep within Asgard until Ragnarok at which point, it is prophesized, he will break free and devour everything he encounters including Odin the All-Father. The thirteenth century epic poem, The Völsunga Saga captured one of the most popular Viking tales of the pre-Christian era. Two thieves, Sigmundr and his son, Sinfjötli, break into an expensive house and find two wolf skins hanging on the bedroom wall that they decide to steal. As soon as they put them on, they are transformed into wolves and overcome with the urge to kill. Several groups of human travelers they encounter pay the price for this. Seven days later they return to human form and burn the skins so that no one ever succumbs to the curse again.

The Irish kingdom of Ossory is famous for being home to shapeshifters of a more ambivalent nature. The kings of the land are said to have descended from Laignach Faelad. They don’t appear to share the bloodlust of his mercenary descendants, however. In his twelfth century study of the land and people of Ireland, Topographia Hibernica (Geography of Ireland) Gerald of Wales relates a story of a traveling priest who comes upon a talking wolf in the woods. After overcoming his initial shock, the wolf persuades the priest to to return with him to the land of Ossory to tend to his sick wife. The wolf explains that the people of Ossory have been cursed by the northern Irish monk, St. Natalis (in some accounts, St. Patrick is the accurser) and as a result they spend seven years in wolf form. If lucky enough to survive they might return to their human form at the end of that period. The priest agrees to follow the wolf home and meets a dying she-wolf. She removes her skin and reveals an old human woman underneath. As she dies, the priest performs last rites and then leaves peacefully.

An eleventh century poem called De mirabilibus Hibernie, ‘On the Wonders of Ireland describes the Ossory werewolves in less sympathetic terms as wicked ones who:

the form of wolves, and rend flesh with wicked teeth:

Often they are seen slaying sheep that moan in pain.

But when men raise the hue and cry,

Or scare them with staves and swords, they take flight

It goes on further to describe Ossorian werewolves as people whose spirit leaves their bodies while sleeping to inhabit that of a wolf. The sleeping human body must not be disturbed or its wandering spirit will be unable to return.

As Europe was Christianized in the centuries following the fall of Rome, the werewolf myth was adapted into the newly dominant worldview. In common folklore, the wolf remained an ambiguous creature, a symbol of both bravery and cunning. For the Church, however, the creature was an unquestionably evil servant of the enemy who was dangerous not just to one’s livestock or even life, but was also a threat to the immortal souls of the faithful. The Bible frequently references the wolf as a shorthand for a deceptive person and the New Testament in particular compares wolves to religious hypocrites who will lead believers astray. Furthermore, Christian thinkers also saw the wolf’s role in Celtic and Germanic lore as part of a pagan tradition that they tended to associate with Satan. To the average person, who lived on the edges of the woods or the desolate steppes, the threat was more tangible. Given the deadly nature of the wilderness, a howling wind might be a sign of a coming storm, or it could be a wolf man getting ready to go on the hunt. A good signal to pull the kids inside and lock the door.

This blend of ideas further developed the werewolf myth. It was during this time that the fundamental association between moon phases and lycanthropy seems to have begun. A fourteenth century English cleric named Gervase of Tilbury wrote the encyclopedic work Otia Imperialia, in which he noted that “certain men change into wolves according to the cycles of the moon.” To my knowledge this was the first written association between werewolves and the moon. It was likely rooted in the medieval belief that an unlucky person who slept under the light of the full moon on certain nights (usually Fridays), might be changed into a wolf. This was hardly the most common means by which a person might be cursed with lycanthropy though. The book also mentions a few other tragic cases of poor souls who were turned into werewolves through either bad luck or simple carelessness. It tells the story of Raimbaud de Pouget, a disinherited knight who once found himself wandering in the woods after dark and as a result became ” deranged by extreme fear,” and “lost his reason and turned into a wolf.” Another victim was cursed after taking off his clothes and rolling naked in the sand. What he was trying to accomplish through this is not entirely clear, but it turns out that engaging in this admittedly strange behavior can have some very dire consequences. Other acts like drinking water from the same spot in a river that a werewolf had previously used, or eating things like lycanthropous flowers or more grimly, the brains of a wolf or an unborn fetus might also cause one to be inflicted with this condition.

In parts of Eastern Europe it was widely believed that the circumstances around an individual’s birth could cause this affliction. The seventh son was particularly vulnerable, especially if he were in turn the son of a seventh son. Children born on Christmas Day were also more apt to become werewolves and special ceremonies had to be performed on holiday babies to prevent this from happening. And of course, the descendent of a werewolf was very likely to inherit the condition. We can probably assume that a seventh son born on Christmas Day that falls on a full moon, who is the child of a seventh son who is a werewolf is almost certain to sprout fur and fangs and go out baying at the moon at some point.

But as Christianity became more deeply embedded in the culture, lycanthropy was increasingly believed to be a product of malfeasance. It was best to avoid using blasphemous language as this could transform a person into a wolf. Angering a witch might also cause one to be struck with a vengeful curse. But sometimes the wicked became werewolves voluntarily. Witches were known to take animal forms, most famously as cats, but often as wolves. They could do so by using a magic potion, special herbs, salves, an enchanted belt, or animal skin to gain the power of transformation, for the small price of signing their eternal souls over to the devil.

Whether through sorcery or bad luck, a werewolf was doomed to its condition unless it could be cured by magical means. It first needed to be identified in its human form which could be done in several ways. A dead giveaway was a pair of thick eyebrows, especially if they formed a unibrow. A werewolf also had hidden fur sometimes under it’s tongue or beneath the skin, that would be revealed only if the suspect was cut.

Werewolves were generally invulnerable in wolf form. Such a condition could only be cured by use of special herbs like wolf’s bane. According to folklorist Montague Summers, a lycanthrope’s curse may be reversed if they are “thrice addressed by their Christian name, or struck three blows on the forehead with a knife, or that three drops of blood should be drawn,” If the the sorcerer who had cursed the werewolf could be found and killed, it would break the spell. Finally, the magical item that caused the transformation could be destroyed. You may have noticed that the most iconic weapon against a werewolf is missing here, but don’t worry, I’ll get to that in short order.

To the vast majority of theologians however this was all a bunch of superstitious hokum. Most high church officials and learned people of the time repeatedly insisted that the werewolf was a merely a metaphor meant to describe a corrupt person who had been led away from God. The first appearance in English of the word “werewolf” comes from The Ecclesiastical Ordinances of King Cnut (1017-1035) that implores the clergy of England to “defend their spiritual flocks with wise instructions, that the madly audacious were-wolf do not too widely devastate, nor bite too many of (them).” The wording of this code was inspired by a bishop ironically named Wulfstan who had recently given the “Sermon of the Wolf” a tirade against the ungodliness and cruelty of contemporary English society, it is generally understood that the code used the concept of the “were-wolf” to mean an outlaw or person lacking in morals. In this case, its bite was akin to temptation by the devil and the beastly transformation is spiritual rather than physical in nature.

Indeed, the concept that a man could transform into a beast was one that did not jibe with church doctrine and was condemned as pagan belief. In the eighteenth book of The City of God, St. Augustine recounts a number of times in the Bible that a human is transformed into another form, but notes it is always God who wills the change. He denies that any human, even when aided by the Devil could wield the same power. Satan and his minions “do not create real substances, but only change the appearance of things created by the true God” and that therefore “can (not) really be changed into bestial forms.” This was both the orthodox opinion of the church and the conventional wisdom of educated people. Accordingly, while medieval bestiaries, field guides of creatures that existed in the wild contained entries for mythical beasts like dragons and unicorns, that everyone at the time believed to exist. Few if any included the werewolf.

Nonetheless, when the church began its centuries-long witch hunt, the debate over the werewolf’s nature – was it a spiritual corruption or a physical curse? – became academic. Blurry lines between good and evil ceased to be a luxury anyone could afford. Spiritual warfare was a fact of life and the Devil’s influence on Earth became an issue that had good Christians living in a state of constant terror. During those dark centuries, roughly between 1450 and 1750 CE, rumors of werewolf attacks spread alongside those of sorcery and devil worship. While thousands of witches were burnt, hanged, or tortured to death, dozens of convicted werewolves also went to their graves at the hands of the authorities.

In fact, one of the major events that most historians view as the opening round of the witch hunts began with the first systematic prosecution of sorcerers in Valais, Switzerland in 1428 that was known locally as “Werewolf Witch Trials”. According to a contemporary chronicler of the events named Johannes Fründ, a spate of missing children and mutilated livestock was the result of witches turning themselves into wolves and committing acts of cannibalism and savage cattle slaughter. The trials kicked off a wave of prosecutions across the continent and cemented the idea that the ancient shape-shifter of legend and lore was a product of the Devil’s black magic. While the prosecution of witches was often carried out under nebulous circumstances and based on flimsy evidence and tenuous accusations, those prosecuted as werewolves usually left a trail of bodies behind.

In 1521, two shepherds in Besançon, France named Pierre Burgot and Michel Verdun confessed under torture to making a deal with a black-clad horse rider that they would serve the devil in exchange for food and the safety of their flocks. They claimed to have attended a witch’s sabbath where they rubbed their bodies with a magical ointment that instantly caused them to sprout fur and become wolves. The two men were overcome by the urge to run across the countryside in search of children to devour. For their crimes they were burnt at the stake.

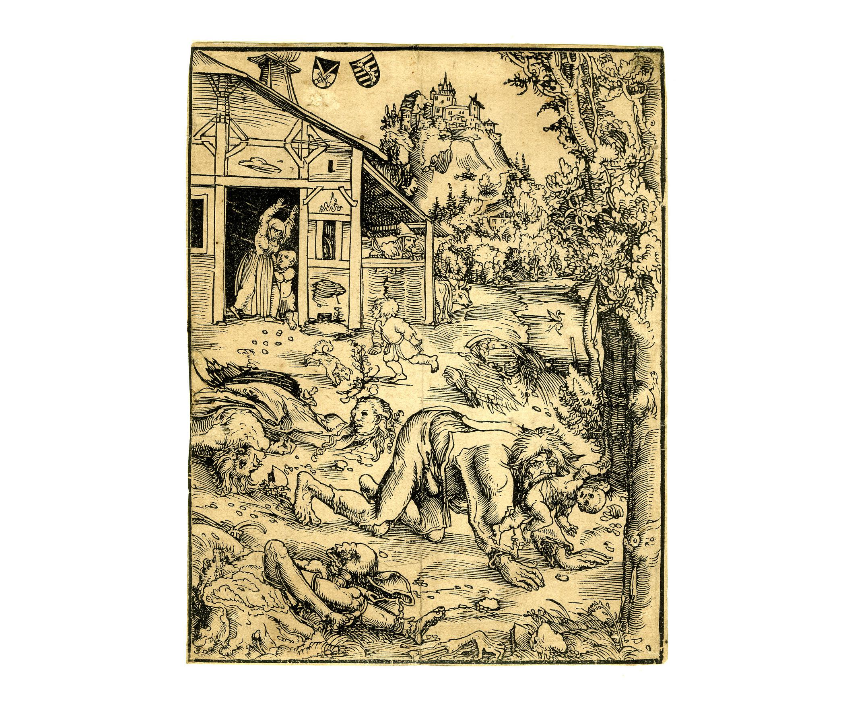

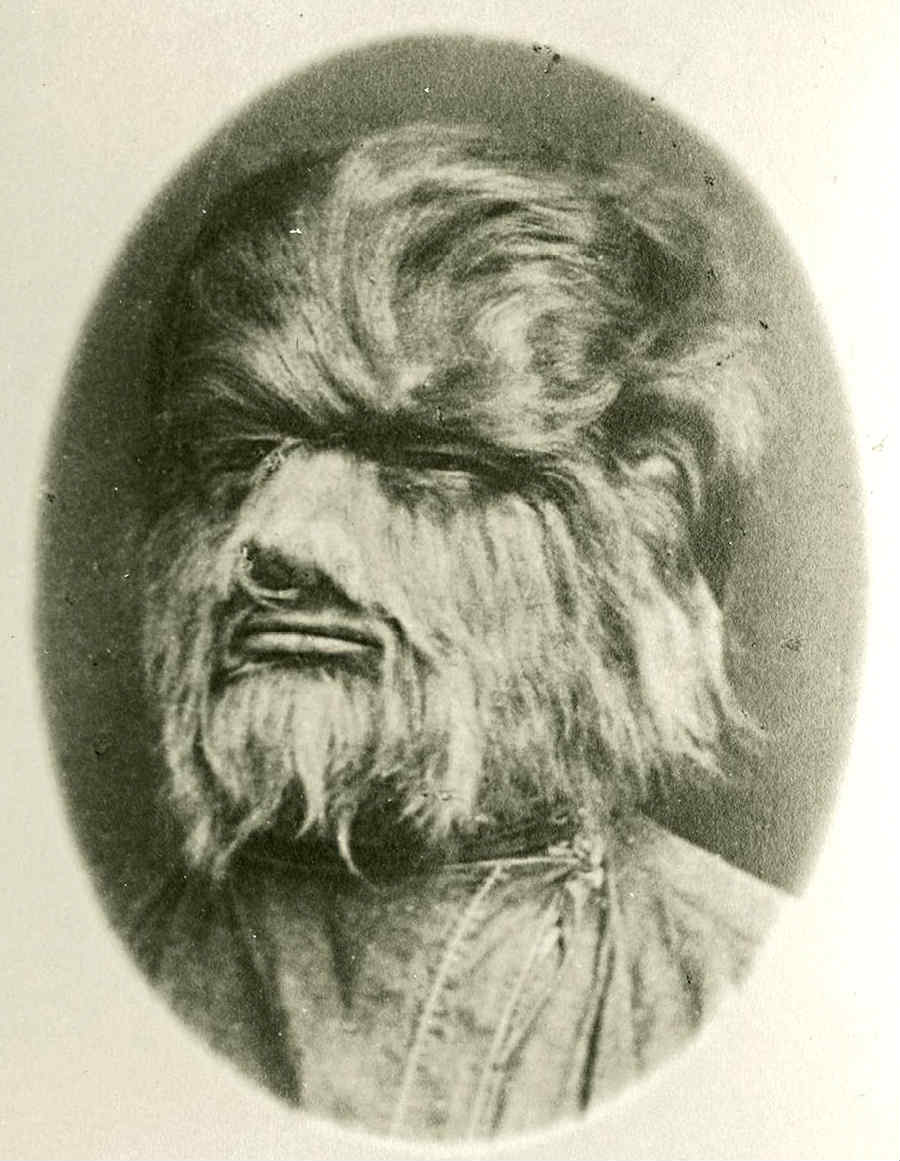

History’s most infamous lycanthropy trial occurred in Germany in the late sixteenth century with the prosecution of Peter Stubbe, the dreaded Werewolf of Bedburg. Beginning in 1582, villagers in the region of Bedburg began experiencing savage mutilation of their cattle. Most assumed rapacious wolves were the culprits, but when children began to disappear, only to be found murdered with their bodies torn apart, it was clear that it was no ordinary wolf in action. At first no one suspected Stubbe, a successful farmer and widower who was well-respected in the community. But when a suspicious-looking wolf was spotted and many members of the community gathered to hunt it they were not ready for what they found. They stalked the creature for several days before finally cornering it and were shocked to find that their beloved neighbor was cowering in the place where the wolf had retreated. Stubbe was tortured on the rack and confessed to all sorts of horrors the locals couldn’t imagine. He had raped and killed thirteen children then torn their bodies to shreds, often eating his victims. He’d had incestuous affairs with several family members including his son who he’d later lured into the woods to kill and eat his brains. He admitted being given by, “the Devil a girdle, which being put on, he forthwith became a wolf”. On Halloween, 1589 he was beheaded after having his flesh removed by red hot pincers and his limbs shattered by axes. His head was hung on a long sharpened pole in the center of Bedburg above the carved likeness of a wolf.

Other stories didn’t go to trial but spread widely and became deeply entrenched in the public imagination. During the summer of 1565 in the fortified Italian city of Mantua the bodies of several young boys turned up in a severely mutilated state. A group of concerned locals reported to the Dominican friars living in the city’s monastery that they suspected the killers were werewolves. They believed the culprits were a pair of gardeners who worked for the ruling Gonzaga family and the friars began the process of interrogation. The Count Cesare Gonzaga became enraged at the insinuation, and in-turn accused the Dominicans themselves of being werewolves. No records exist to suggest whether anyone was actually punished for these crimes.

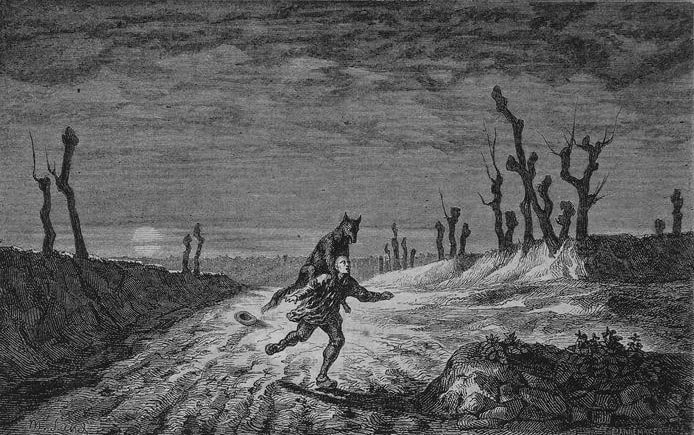

In France where the locals called lycanthropes le loup-garou, werewolves became a major problem. In the 1760s the southern province of Gévaudan, a series of grisly deaths haunted the countryside and left as many as a hundred victims. In the late spring of 1764, a young shepherd named Jeanne Boulet was tending her family’s flock of sheep in the forest when a creature she described as “like a wolf, yet not a wolf” charged at her. She was able to escape, but just barely. For the next year attacks continued and locals were mauled, went missing, or turned up dead and half-eaten. One of the more famous incidents occurred in August 1765 when Marie Jeanne Valet, a nineteen year old girl was crossing the River Desges with her sister when they were attacked by the monster that was now being called The Beast of Gévaudan. She fought it off with a bayonet, stabbing the creature and forcing it back into the forest, earning fame across France as a result. But the attacks continued and most who encountered the wolf weren’t so lucky. The public outcry became so intense that King Louis XV sent troops to region. After a massive mobilization of hunters and soldiers, several large wolves were killed giving locals brief hope that the reign of terror had ended. One large gray wolf was shot by the king’s personal hunter, François Antoine and then stuffed and mounted at Versailles. Soon thereafter, however, two young boys were killed and it was clear that the Beast was still lurking. It was up to a local hunter by the name of Jean Chastel who killed another large wolf, according to some accounts with a silver bullet, that was cut open to reveal a stomach filled with human remains. According to some witnesses, the corpse had some rather un-wolf-like characteristics. No one has every confirmed the cause of the killings, but to most contemporaries there was little doubt that the monster was a werewolf.

But even those who put thousands to death for practicing black magic continued to argue over the question of what a werewolf actually was. Henri Bouget, a judge who tried dozens of witchcraft and lycanthropy cases in Abbey of St. Claude from 1596-1609 wrote Discours des Sorciers, one of the most important legal guides for carrying out witch trials. He dedicated a section of the book – “Of the Metamorphosis of Men into Beasts” – to trying to explain why werewolves were terrorizing the countryside. Recounting a number of horrific cases he’d personally adjudicated, he described incidents of child murder, mutilation, and cannibalism committed by people who testified they’d acted while in the form of wolves. One striking tale that resembles a recurring theme in werewolf fiction today occurred in 1588 and concerned a huntsman who encountered an unusually cunning wolf while traveling in the forest. The beast attacked him, but was immune to his bullets and the huntsman survived only by cutting off the wolf’s paw with his hunting knife. After leaving the woods the hunter came to a homestead and told the head farmer about his encounter. But when he tried to pull the severed paw out of his bag to show his trophy, he instead found a human hand wearing a wedding ring. The farmer recognized with horror that the ring belonged to his wife. They ran in to check on her only to find her in the kitchen nursing the stump of her arm where her hand used to be.

Nonetheless, Bouget defended church doctrine arguing unequivocally that actual transformations of man to beast as his defendants so often so often claimed to have experienced was not possible under the laws of God. He reasoned, however that demonic forces could not only fool a person under their influence that he’d been transformed into a wolf, but also bewitch the lycanthrope’s victims and any witnesses into believing they’d seen a wolf man.

Heinrich Kramer author of the infamous guide to witch hunting Malleus Mallifecarum addressed this issue and suggested that lycanthropes were actually possessed wolves who gained the intelligence of their demonic masters. The treatise De la Lycanthropie, Transformation, et Extase des Sorciers (Of Lycanthropy, Transformation, and Sorcerer’s Ecstasy, 1615) written by demonologist, Jean Nynauld, was probably the first book dedicated exclusively to the problem of werewolves. Nyanauld argued that werewolf attacks were real, but they were committed by a sorcerer who had ingested hallucinogenic herbs that caused him to dream that he’d transformed into a beast.

But there were learned men who fully believed that Europe was plagued by actual werewolves. Jean Bodin rejected the common wisdom of his colleagues and was adamant that these transformations were literal. He recollected a number of cases in his 1581 book, De la Démonomanie des Sorciers (‘On The Demon-Mania of Witches’) in which he argued against the Augustinian claim that the devil could not perform the same miracles as God, writing “there is no evidence that God did not give this power to Satan.” For this, his book was placed on the pope’s list of heretical works. Nonetheless, it was widely read and translated into multiple languages. Its message almost certainly rang true to a wider audience who were terrified of the howling noises they heard outside at night.

Johann Weyer (1515-88), a student of the great humanist, Erasmus of Rotterdam followed his mentor’s approach and sought a more rational explanation for the epidemic. During this time, the term lycanthropy came into popular usage and though it is etymologically synonymous with “werewolf” (the former is Greek and the latter German and both translate simply to “wolf man”) in practice it became associated with the idea that werewolves were people suffering from a disease of the mind. Weyer pointed to the system of humors that was medically dominant at the time and suggested that lycanthropes suffered from melancholia, an excess of black bile in the body that could result in depression and hallucination. This insight was not new – it was mainstream opinion of his day that lycanthropy was a melancholic condition – but while most authorities believed this imbalance was the result of the victim inviting Satan into their lives. Weyer cut out the black magic altogether and saw the ailment in completely medical terms and recommended treatment rather than punishment.

Over time, Weyer’s view became dominant and the authorities began to respond more humanely to cases of lycanthropy. In 1603, a teenage boy named Jean Grenier living in southern France came upon a group of peers who were discussing a recent deadly wolf attack on a girl named Marguerite Poirier. Grenier confessed to them that he had been the wolf who attacked her, a state he achieved by wearing a magic pelt. He then told them all sorts of stories about how he had developed a taste for human flesh, stolen a baby from a crib and eaten it while in wolf form. Since Grenier’s accounts were corroborated by a number of missing children he was arrested, tried and determined to have been possessed by a demon, and initially sentenced to death like any other servant of Satan. The conviction was commuted however, in recognition that Grenier was clearly mentally unbalanced, and instead he was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in a monastery in Bordeaux where he remained until his death in 1611.

Perhaps the most unusual case to come out of those times happened in Livonia in 1691 in which a man known to history only as Thiess was brought before a court on charges of lycanthropy, a condition to which he readily admitted. He departed from most other defendants in these sorts of cases, however by claiming that he along with several other werewolves had indeed stolen livestock, but they cooked their flesh before eating it. Even more unusual, he stated categorically that he and his fellow wolf men were actually servants of God who journeyed to hell three times a year to fight Satan and his minions in order to protect the village crops from evil. Theiss was given a sentence of twenty blows and let off to live his life. Presumably, the court saw the defendant as mentally unstable, but mostly harmless.

In the ensuing centuries, lycanthropy became rarer, but has never fully disappeared. The nineteenth century Spanish serial killer, Manuel Blanco Romasanta, the so-called “Werewolf of Allariz” was sentenced to death for murdering nine people. He claimed, he’d done so after transforming into a ravenous beast. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by royal decree in part because it was recognized that he was the victim of severe mental illness, and physicians wanted to study his case in more detail.

Even today, the condition still comes up from time to time and have come to be associated with “schizophrenia, psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, and other psychotic disorders.” It is very likely that many of history’s lycanthropes were afflicted with the same personality disorders as the people we today recognize as very human serial killers. In addition to the psychological aspects of lycanthropy, some modern researchers have argued that there are physical conditions that may have helped promulgate the werewolf myth. The most obvious of these has been linked to a rare disease called porphyria, a blood disorder that can cause both an aversion to sunlight and excessive hair growth.

Whether in myth, folklore, theology, or psychology, the werewolf as I’ve discussed so far is probably somewhat familiar to any horror fan. Stories about humans who turn into wolves is a pretty standard occurrence in books and movies that we’ve all grown up with. But what of the full moons and silver bullets that are central to most werewolf stories we know? What of the pentagram on the palm that is sure sign that an unlucky man or woman is meant to morph into a wolf when the full moon shines? What about the person bitten by such a monster, destined to become one too? And though I’ve shown some hints of it in the folkloric traditions discussed above, what about the tragic burden placed upon those afflicted with lycanthropy? These ideas were born as the monster moved out of the realm of collective lore and into the imagination of individual authors.

It feels like I reference the oldest fiction story known to humanity, namely The Epic of Gilgamesh every time I discuss the origins of some modern day trope. Well I’m going to do that again here. That’s because the ancient Mesopotamian poem features a segment in which the goddess Ishtar expresses her desire for the story’s titular hero. But Gilgamesh spurns her advances out of a strong sense of self-preservation noting some of the horrible things she’d done to former lovers including turning a herder into a wolf so that “his own shepherds not chase him. ” While hardly an account of a dangerous shape-shifting beast, it does present the transformation of man into wolf as a terrible curse, and remind us just how old the idea has been floating around in our collective imagination.

Closer to our modern horror monster is a two page section from Gaius Petronius’ Satyricon, a first century Roman satire. In a passage known as the story of Niceros, a young former slave recounts a tale of a nighttime journey gone wrong. Along with a traveling soldier, Niceros comes to a graveyard where they stops to rest. While the moon shines overhead “like high noon” the soldier removes his clothes and urinates around himself in a circle. He is instantly transformed into a wolf and howls before he races off into the nearby woods. Niceros draws his sword and rushes after his erstwhile travel companion. After a short time he ends up at his lover’s house, his originally intended destination. When he arrives he finds the household in a state of panic after having been attacked by a wolf who killed the family’s sheep. Luckily, they were able to drive the beast away when a family slave pierced the beast’s neck with a spear. Niceros returns to the graveyard to find that the soldier’s clothes are gone and in their place a pool of blood. Upon returning to his master’s house, Niceros finds the soldier lying in bed while a doctor treats a wound in his neck.

I’ve painted the werewolf in the Christian era as a monster of pure evil, but the creature sometimes appeared in medieval literature with a more sympathetic tone that foreshadowed its frequent depictions as an unfortunate victim in modern fiction. The twelfth century Anglo-Breton poet Marie de France included one such tale in a her most famous collection of lais. In “Bisclarvet” (“Lay of the Werewolf”) she begins by noting the conventional understanding of the nature of the beast:

A werewolf is a savage beast,

While the fury’s on it, at least:

Eats men, wreaks evil, does no good,

Living and roaming in the deep wood.

Yet the story’s lycanthrope does not match this description at all. Unlike Lycaon who is punished for his wickedness or the unfortunate souls burned at the stake for their lycanthropy, Bisclarvet is a nobleman cursed with a terrible condition who manages to maintain his gentle nature. When the wife learns her husband’s secret she scheme’s along with an ambitious knight to keep him trapped in werewolf form so she can claim the estate for herself. Her husband goes deep into the forest when his time comes to transform and she follows him, stealing his discarded clothing, without which he can’t return to human form. A year later, the king is riding in the woods when he comes upon an unusually friendly wolf and takes it in. After consulting a wise advisor, he realizes that this wolf is in fact, the missing baron, and uncovers his Bisclarvet’s wife’s secret plot. Soon, Bisclarvet’s clothes are returned to him and he reclaims his kingdom and they all live happily ever after. Except for the wife; the werewolf devours her.

The werewolf as we know it today came into its own during the nineteenth century. It was a time of massive urbanization which brought country folklore to the cities and these tales soon became an object of great interest to scholars looking to preserve their people’s folk histories. Folklorists like Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm gathered these ancient stories and published them in collections of fairy tales and children’s fables. Many were cautionary tales meant to warn young listeners of the dangers lurking in the forests often preserving the fears of previous generations. There were many witches, but there was also a recurring figure we now know as the “Big Bad Wolf” a cunning, usually talking anthropomorphic lupine antagonist bent on eating children. He was featured most famously in “Little Red Riding Hood” but also in stories like “The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids”. The same figure appeared in the English fairy tale, “The Three Little Pigs” and updated versions of Aesop’s ancient fables like “The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing”. Though none of these stories feature the Big Bad Wolf changing to a human, his anthropomorphic characteristics are very reminiscent of the ancient wolf/man hybrid archetype from which the werewolf was born.

At the same time, the spooky lore of migrants from the countryside became the stuff of urban fiction writers, and the werewolf along with many modern horror tropes, came out of the Gothic literature of the period. As far as I’m aware the earliest fictional werewolf tale was Richard Thomson’s “The Wehr-Wolf: A Legend of the Limousin” first published in 1828. It is a retelling of the old story of a hunter who is attacked by a wolf and severs a paw only to find that a local recluse has turned up missing arm. “The Man-Wolf” a story written by Leitch Ritchie three years later about a knight’s quest to find a cure for his lycanthropy is perhaps the first werewolf novel. “Hugues, the Wer-Wolf” Sutherland Menzies’ 1838 tale of the last descendent of a cursed family who finds in an old family chest with a strange garment that turns him into a wolf and gives him the power to seek vengeance on the townspeople who have long persecuted his family. “The White Wolf of Hartz Mountains” (1839) by Frederick Marryat, a story that drew on the lore of Transylvania nearly sixty years before that old kingdom was popularized as the vampire homeland in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It tells of a family doomed by a mysterious white wolf who haunts the woods around their secluded cabin, a wicked stepmother, and a family curse that follows the family’s youngest son across the globe.

In the 1840s and 50s the rise of the penny dreadful brought the high brow Gothic to working classes of London. G. W. M. Reynolds, is largely forgotten today, but at the height of his fame he outsold his more well-remembered contemporary, Charles Dickens. He began his career in the pages of penny dreadfuls and is purported to been one of the anonymous authors who worked on the long-running serial story Varney the Vampire. He broke away from the grind and added Wagner the Wehr-Wolf in 1847. It is a Faustian tale of a man who gains great power, but at the price of becoming a werewolf. “The Other Side: A Breton Legend” by Count Eric Stenbock written in1893 begins by recounting a local legend that resembles the ancient stories of tribes of werewolves like the Arcadians or Neuri. Hector Hugh Munro, better known as “Saki” wrote a spiritual sequel to Stenbock’s story called “Gabriel-Ernest” (1909) about a mysterious boy that shows up in the woods near another village that is also bound by a mysterious brook.

Around the turn of the century a number of the authors who would become the forbears of twentieth century horror would write werewolf stories. Better known for his 1897 novel, Dracula, Bram Stoker published “Dracula’s Guest” in 1914, a story widely rumored to have originally been written as the first chapter of Stoker’s novel features a large beast that is chased off by soldiers who identify it as “”a wolf—and yet not a wolf” a quote that harkens back to one witness’ account of the infamous Beast of Gévaudan case that terrorized France in the 1760s. Algernon Blackwood was a huge influence of H.P. Lovecraft and perhaps one of the masters of writing wilderness horror. His 1920 short, “Running Wolf” is set in such a place, the wilds of Canada where a vacationing hotel clerk finds himself followed by a strange wolf that watches him constantly from a distance. Arthur Conan Doyle played around with the tropes of werewolf fiction in one his 1890 proto-slasher murder mystery, “A Pastoral Horror“.

Very few of these stories have had the lasting power of Frankenstein or Dracula, and really, I can’t think of a werewolf novel or story that does. Perhaps two come close. Clemence Housman, a British suffragist and artist wrote The Were-wolf in 1896 (it was serialized six years earlier), a lycanthrope story set in Scandinavia about a strange woman named White Fell who visits an isolated farmstead. Soon members of the family begin to disappear and one brother is suspicious that the mysterious visitor who goes out into the cold every midnight, might be something other than human.

But arguably the closest to achieving iconic status was The Werewolf of Paris published by Guy Endore in 1933. The novel is set in France during the tumultuous days of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. It focuses on the life of a national guardsman named Bertrand Caillet who is born a werewolf by virtue of an unlucky combination of his birth date on Christmas Eve and the fact that he was conceived when his mother was raped by a priest. As a result corpses turn up wherever he goes, but this mostly goes unnoticed in the bloodbath that Caillet finds himself living through in 1870s Paris. The book like so many werewolf stories finds its way into deeply tragic territory and may have become more famous had it been adapted earlier into a film. It was published during the heyday of 1930s monster movies and it almost ended up being adapted along with famous novels like Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, but it was not to be.

Werewolves became a stock character in the pulp magazines of the early twentieth century, notably James Blish’s short story “There Shall Be No Darkness” that combined the ancient myth with modern science in a mystery format. They appeared constantly in the horror comics of the 1950s and they even got to star in Marvel’s 1970s series Werewolf by Night that featured a somewhat super-heroic lycanthrope named Jack Russell (who was only coincidentally named after the dog breed) and was written at times by the aptly named, Marv Wolfman. There have also been plenty of novels published since that time featuring werewolf characters. Among some of the most popular were The Wolfen by Whitley Strieber, Stephen King’s “Cycle of the Werewolf“, and Wolf’s Hour by Robert McCammon. Several stories in Angela Carter’s collection, The Bloody Chamber feature wolves or werewolves and Anne Rice even wrote a werewolf novel called The Wolf Gift in 2012. Writers continue to publish novels about lycanthropes that reach wide audiences, most notably 2011’s The Last Werewolf by Glen Duncan and Those Across the River by Christopher Buehlman that both received mostly positive reviews for their modern depictions of this ancient monster. Werewolves have appeared as secondary characters in the works of JRR Tolkien and JK Rowling., But arguably, Endore’s novel was the last great work of literature to the do the heavy lifting on this trope before the mythmaking moved to the medium in which the monster would truly thrive.

Because the central premise of the werewolf myth involves a transformation from human to wolf form, depicting them presented a unique challenge to early filmmakers. Vampires looked like people with fangs; in fact, in the early Dracula films they didn’t even use fangs. A mummy required a lot of makeup as did Frankenstein’s monster, but once applied it didn’t really pose a technical problem to production other than the major discomfort it inflicted on the actors who wore it. Ghosts were a little trickier, but pioneering filmmakers figured out how to overlap film as far back as the 1890s in order to create the appearance of translucent entities on the screen. But given the technological restraints of early twentieth century cinema, the wolf to man metamorphosis was not easy to portray.

The earliest example of lycanthrope in film was a 1913 Canadian short called “The Werewolf” that was based the skin-walker lore that I discussed above. The story of a Navajo girl named Watuma (Phyllis Gordon) who transforms into a wolf to avenge the death of her father at the hands of white settlers was unfortunately lost when all prints were destroyed in a fire in 1924. It featured a single transformation scene by using a dissolve between a shot of Watuma and some stock footage of a wolf. The 1914 film “The White Wolf” also had a native American protagonist and was likewise lost. Le Loup-Garou (1923) and Wolf Blood (1925) are takes on the legend based largely on the European tradition. The former was a lost French production that despite its name doesn’t feature any supernatural elements, but rather blurred the line between vicious human behavior and that of a wolf, while the latter (which is the earliest surviving werewolf movie) was about a logger who is transformed after receiving a blood transfusion from a wolf.

Like most good monsters that made the transition from Gothic literature to horror cinema icons, the werewolf’s journey would pass through the lots of Universal Pictures. The studio had box office hits in 1931 with Dracula and Frankenstein, and decided pretty quickly that they needed to follow up with a werewolf movie. The title of “The Wolf Man” was quickly chosen by producers and handed to French writer and director Robert Florey who planned to use the story as another Boris Karloff film after his success playing Frankenstein’s monster and the immortal priest Imhotep in The Mummy. Florey’s first treatment outlined a story about a bewitched boy who is raised by wolves and goes on to slaughter his adopted family. The subject matter was too dark for Universal’s executives so the film was shelved.

It was four years before Universal would get their lycanthrope to audiences, and when they finally did, it was without Florey or Karloff (who was busy shooting The Bride of Frankenstein). The final version, the first “talkie” featuring this legendary monster, was 1935’s Werewolf of London about an English botanist played by acclaimed theater actor Henry Hull who is bitten by a strange creature while traveling in Tibet. Upon his return home he is transformed into a werewolf who terrorizes London until he is shot to death by a normal lead bullet. Its transformation effects were created by Universal’s chief makeup artist Jack Pierce who was responsible for Karloff’s frightening appearance in Frankenstein. Due to the lack of flexibility of the makeup materials used in those days, Pierce wasn’t able to construct a convincing snout. Instead, Hull’s look was more human than wolf, in some ways resembling the look of Mr Hyde in Paramount’s 1931 film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. His original design used more fur, but the studio wanted to make sure Hull maintained some of his human appearance, so the lupine features were dulled, though still spooky. To show the metamorphosis Hull’s character walked across a room filled with pillars that obscured him from the shot for a few seconds at a time. As he emerged on the other side of each pillar, he showed signs of change until the transformation was complete.

The film didn’t make waves the way Universal had hoped, but it was not the studio’s last stab at werewolf movies. The studio’s follow-up would prove to be every bit the myth-maker that its earlier lineup of monster films had been. The 1941 classic, The Wolf Man starred Lon Chaney, Jr. as an American born descendent of British aristocracy named Larry Talbot who comes home to the family estate in Wales only to be attacked by a wolf and cursed to become a murderous lycanthrope. It has everything one could want in a classic monster movie – old European castles, foggy moors, and suspicious villagers. Its transformation scene is a bit more advanced by the standards of the day. It used the lap dissolve technique of filming the actor, cutting the camera, applying makeup and filming again. Pierce did this a few times, fading between takes to give the appearance of a change happening over time. The big transformation scene focused on Chaney’s feet and there was a de-transformation at the end of the movie using the process in reverse that seem a bit hokey today, but it would establish the most feasible technique for turning a person into a wolfman that would be used for decades.

Chaney’s acting is as good as his acting ever got and he was backed by a cast that included Claude Rains, Bela Lugosi, and Maria Ouspenskaya in an iconic performance as the gypsy woman, Maleva. Jack Pierce got to use his more canine design he’d originally come up with for The Werewolf of London, and George Waggner’s direction was, in my opinion, the best of the first wave of Universal horror. But the true star of the movie was screen writer Curt Siodmak. The German born writer sought to create a sense that his story was pulled from the pages of folklore. He achieved this beyond his wildest dreams and introduced elements to the werewolf mythos that many people even today assume were born of ancient traditions rather than the mind of a single man. He conceived of the pentagram in the palm of a young girl’s hand that shocks Maleva, who knows it is a sure sign that she is to be the victim of a werewolf. He also wrote the iconic little poem that sounds like it may have been recited by medieval clergymen:

Even a man who is pure in heart,

And says his prayers by night,

May become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms,

And the moon is full and bright.

This little line cemented the relationship between the werewolf and the full moon that had only been hinted at in folklore. Most importantly, Siodmak is the man responsible for giving the creature’s its most effective weakness when he wrote the ending in which Talbot’s father bludgeons him to death with a cane tipped with wolf’s head carved of pure silver.

Part of The Wolf Man‘s lasting legacy is the ideas it helped to cement in the public imagination the tropes of just about all werewolf stories to follow. Nonetheless, after the decline of Universal’s Gothic monsters in the 1950s, werewolf movies became somewhat rare. They did manage to sneak into the decade’s parade of bug-eyed monsters from space and radioactive mutants here and there by filmmakers who shoehorned the creature into a sci-fi setting. The lycanthrope is a product of archetypal mad scientists in the 1956 The Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Werewolf the following year. The latter of these helped to spearhead a movement of horror movies marketed to youth audience.

Hammer Studios in London began to make their mark in the late 1950s with remakes of Universal horror films Dracula and Frankenstein and The Mummy that all spawned many sequels. They only dipped once into the werewolf subgenre with the 1961 film, Curse of the Werewolf a loose adaptation of Guy Endore’s novel The Werewolf of Paris that gave Oliver Reed his first leading role. It was Hammer at its best and makes one wish it too birthed a popular franchise. The 1970s took the werewolf along into the strangeness of the decade with Werewolves on Wheels (1971) about a biker gang who is transformed into a pack of lycanthropes by a cult of Satanic monks and Amicus Productions’ 1974 sci-fi whodunit tale, The Beast Must Die, starring Peter Cushing.

But as horror was entering into the golden age of the 1980s, the werewolf was about to make its mark. 1981 has come to be known as “The Year of the Wolf” because in that year two of the most influential films of the subgenre were released. Not only did these films push the boundaries of the wolf man story, but they took advantage of the decade’s major advances in the use of practical effects. This development helped filmmakers overcome the hurdles that earlier generations of cellular werewolves faced pushing them light years ahead of the old camera tricks used to change Lon Chaney Jr into a guy with furry feet through lap transitions.

In March of that year, Joe Dante, an acolyte of the legendary B-movie director Roger Corman, revisited the wolf man trope but brought a grit to the story with his adaptation of the novel, The Howling. The story centers around a television anchor named Karen White who becomes a target of Eddie Quist, a brutal serial killer. The police manage to kill him, but suffering from the trauma of her ordeal, Karen’s therapist sends her to a secluded resort called “The Colony”. There she learns a number of terrible secrets, and worse, Quist returns, changing before her eyes into a werewolf. Never before had the world seen such a transformation on screen. With effects wizardry of a young artist named Rob Bottin, The Howling‘s werewolves changed into very frightening anthropoid wolf men with long canine snouts and truly monstrous features that contrasted sharply with the tamer monsters audience had experienced in the previous decades.

Later that year, John Landis director of such renowned comedies as Animal House and The Blues Brothers decided to throw his hat in the horror ring (though in so doing he would not forsake his comedy roots). In August of 1981, An American Werewolf in London was released. David and Jack, two travelers from the United States backpacking in rural England are attacked one foggy night by a large wolf. Jack dies, but David escapes with a few wounds. Jack is the lucky one. A few nights later, David finds himself staying at the flat of Alex, the nurse who helped him recover from his injuries he changes into a wolf in her living room while Sam Cooke’s “Blue Moon” plays in the background. It is simply one of cinema’s most incredible displays of special effects courtesy of the inimitable artist, Rick Baker. Where his forbears struggled to create a wolf look, Baker does not shy away from showing David’s face stretching into an elongated snout as he becomes a large four-legged wolf.

Living in the shadow of those two monstrous films, that same year saw the release of Wolfen, a story that borrows heavily from skin-walker lore and Larry Cohen’s B-movie sleeper, Full Moon High. The 1980s would also host classic horror movies like Silver Bullet, The Company of Wolves, and a bunch of Howling sequels. But perhaps the most telling example of the werewolf’s arrival to iconic status was that it transcended the horror genre with the blockbusters Teen Wolf and The Monster Squad. The rest of the century was rounded out by the 1994 Jack Nicholson film, Wolf that brought cinematic respectability to the werewolf trope. The 1996 film Bad Moon took another stab during a time when horror was on the wane and gave audiences little reason to return to the genre. Landis returned with a sequel, An American Werewolf in Paris that didn’t quite land. And there were more Howling sequels.

The twenty first century has been a time of horror renewal and the werewolf film has managed to roll with the changes. Beginning in 2000 with John Fawcett’s masterpiece, Ginger Snaps, an angsty teen story that gave the werewolf the same sort of cool factor that The Craft did for witches. A few years later Dog Soldiers, Neil Marshall’s tale of a rural Scottish werewolf clan who attack a squad of British soldiers on a training exercise is truly frightening. In the last few years, a slew of werewolf movies has proven that the monster is alive and kicking in the modern world. Late Phases (2014) Slice (2018) When Animals Dream (2014), Wer (2013), The Wolf of Snow Hollow (2020), horror comedy, Werewolves Within (2021), and this year’s The Cursed have all shown that tales of humans who are cursed to become wolves still has plenty of room for storytellers to present in fresh and diverse ways. There’re also a couple of series featuring werewolves that have penetrated a mass audience, namely Underworld and Twilight, but I don’t have anything to say about those.

I want to end by circling away from the fictional werewolf back to the real world. We have, of course, collectively moved past ancient superstitions about humans turning into wolves, but the idea has managed to poke its head through the veneer of modernity from time to time. In 1887 a group of lumberjacks in northern Michigan spotted a seven-foot tall canine creature walking on hind legs with amber eyes. In the ensuing decades, many people have reported run-ins with the monster that has become known as the Dogman. In rural Wisconsin, the so-called Beast of Bray Road has been spotted roaming in the woods multiple times since the 1930s, most famously when a car ran into a large wolf-like creature with glowing red eyes in the 1980s that left major scratches on the vehicle. In 1994, Terry and Gwen Sherman a family of non-native farmers moved onto a Utah property that had come to be known as “Skin Walker Ranch” because according to legend, the local Navajo and Ute peoples avoided the area believing it was haunted. The Shermans report seeing lots of strange phenomena, including wolves acting in very bizarre, almost human-like ways. They sold the property two years later and it has become a center of paranormal speculation.

These are just a sampling of legends that persist around the world about wolf-like beasts, perhaps cursed or malevolent humans have taken lupine form. Do these stories suggest that lycanthropy is possible in a literal sense? I agree with the witch hunters of early modern Europe on very little, but I think we are in accord that it is impossible for humans to transform into other animals. But I’m not too surprised that even today there are those who are more than a little bit open to the idea that they’ve seen human/wolf hybrids stalking the forests at night. Maybe it’s is easier to believe that when we engage in cruelty, aggression, or murder it is the pull of some inner beast than it is to accept that we are ourselves animals possessed of all the qualities of the creatures that stalk the wild. That is why this legend has persisted for millennia and continues to be a source for our scariest fiction.

And when you do dress up for a Halloween party (as a werewolf or anything else) don’t you like to hear some great spooky music? Thankfully, there’s a long history of season-appropriate horror music and that’s just what I’ll be looking at next week!

It’s a pleasure to see you return after a long hiatus. This is an excellent article! It was well-researched and a true joy to read.

Thanks Jason! I’m glad you enjoyed it! I’ve got four more coming out this month.

I’d also like to draw your attention to another blog that I recently discovered. I feel that a lot of the articles that it covers, such as Halloween-related stuff and comic books, are right up your alley: https://lewisrhystwiby.wordpress.com/